We use to think of hospitals and clinics as almost history-free zones. But sometimes medical historical images, artefacts and records show up in the most unexpected medical spaces.

Like last week, when I spent a couple of days with our daughter in the neonatal clinic at the Danish National Hospital, i.e., where they care for babies that are born too early (down to 24th gestation week!) and other newborns with more or less serious medical conditions (fortunately ours was a less serious case).

The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators, CPAPs, automatic infusion pumps. Beep-beep everywhere. Definitely a mobile free zone, and much more so than in an aircraft: the staff probably meant it seriously when they said that a single phone on standby can stop all the infusion pumps in the ward!

The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators, CPAPs, automatic infusion pumps. Beep-beep everywhere. Definitely a mobile free zone, and much more so than in an aircraft: the staff probably meant it seriously when they said that a single phone on standby can stop all the infusion pumps in the ward!

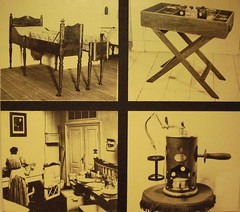

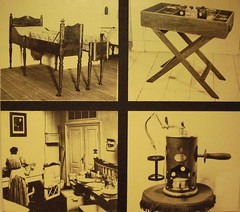

But they had more on show than science fiction-looking technology for our future collections. Behind the toilets, in a short hallway leading to the parents’ day area, I discovered four large images of museum artefacts — in fact, images of 19th century objects on display in the 1970s permanent exhibition of the former Medical History Museum (now Medical Museion):

The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements.

The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements.

None of the items on the pics have much to do with neonatal care and the print quality is not exactly good. Yet some time, someone (maybe the head of the clinic?) decided to hang them there, partly stuck away. Why? To add a slight historical touch to the high-tech ambience of the clinic? To create some balance?

These images made me think of the geography of the medical historical heritage. The medical heritage is not just a heap of things in medical museums — it is a dynamic field, which is distributed and put to use in a variety of spaces over time. Medical historical images, artefacts and records circulate between patients, medical staff, manufacturers, clinics, hospital storage rooms, archives, collections, and exhibitions (and are sometimes pulled out of circulation and deposited as heritage sediments in closed museum repositories).

Heritage is a very different thing when it appears in designated museums like ours (a sort of ‘temple’ for medical heritage) and when it is distributed, even in the form of images, around the clinics of the Danish National Hospital and in other hospitals, institutions, organisations and private homes in the region, where it functions more like memorial shrines.

The spatial distribution and dynamic relation between the ‘worship’ of heritage in temples and shrines is an interesting topic. The way medical museums collect, manage, display and make sense of this heritage is very much dependent on how the overall geography — including the production, circulation, distribution, consumption, performance and eventual destruction — of local heritages is understood and conceptualised.

Anybody willing to expand on this? Anyone out there who can develop his/her thoughts on the ‘geography of the medical heritage’?

“Part of a more general ‘spatial turn’” (i.e., yet another turn!), the explicit aim of the project is to draw attention to the way that space matters in the production of science and technology and to the implications of the circulation of expertise and materials in the situating of science and technology.

“Part of a more general ‘spatial turn’” (i.e., yet another turn!), the explicit aim of the project is to draw attention to the way that space matters in the production of science and technology and to the implications of the circulation of expertise and materials in the situating of science and technology.

The

The  The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators,

The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators,  The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements.

The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements. But linguistic and computer analogies are not very helpful when it comes to the proteome with its estimated half million or so specific protein-protein interactions (the ‘

But linguistic and computer analogies are not very helpful when it comes to the proteome with its estimated half million or so specific protein-protein interactions (the ‘ The second image is also a ‘cogwheel model’, in this case of a protein complex in yeast cytoplasm that contributes to mRNA decay (credit: European Molecular Biology Laboratory; from

The second image is also a ‘cogwheel model’, in this case of a protein complex in yeast cytoplasm that contributes to mRNA decay (credit: European Molecular Biology Laboratory; from  Our colleagues in Leeds (i.e., the Division of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Leeds and the Thackray Medical Museum) are re-advertising a studentship for a project on nineteenth-century midwifery instruments. The successful candidate will be part of a group working on 19th-century topics connected with museums and material culture.

Our colleagues in Leeds (i.e., the Division of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Leeds and the Thackray Medical Museum) are re-advertising a studentship for a project on nineteenth-century midwifery instruments. The successful candidate will be part of a group working on 19th-century topics connected with museums and material culture. Eager to train myself for the role of a future biocitizen, I’ve looked in vain for a guide to bars, cafés and restaurants with medical motifs. I mean, if

Eager to train myself for the role of a future biocitizen, I’ve looked in vain for a guide to bars, cafés and restaurants with medical motifs. I mean, if