As I wrote in a previous post, our little newborn was transferred from the maternity ward to the neonatal clinic to keep her under observation for a couple of days (because of an infected thumb; never neglect small wounds in small children, they have a weak immune system!).

To keep my paternal anxiety under control, I began to look around and take some photographs of this peculiar, high-tech medical space. And what especially triggered my curiosity (besides the mysterious use of old historical images, see earlier post) was the monitoring system.

‘Our’ ward team cares for twelwe patients, from very prematurely born (down to 21 weeks!) to newborns with all kinds of medical conditions, most of them much more serious than our infant’s. Each is kept under surveillance with respect to heart beat frequence, oxygen saturation level, blood pressure, and so forth.

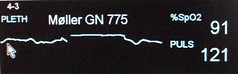

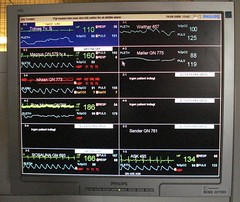

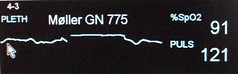

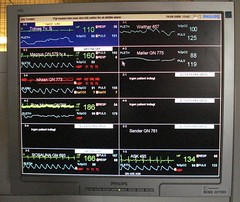

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’.

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’.

If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient.

If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient.

What intrigued me wasn’t the system as such, however — I guess such monitoring platforms (in this case Philips IntelliVue MP90) are pretty much standard equipment in most neonatal wards and emergency medicine rooms in the rich parts of the world — but rather how the system’s visualization of the monitored vital data began to change my conception of our newborn’s identity. Within a few hours, I went from thinking about her in terms of mundane identity to constructing an entirely new, biomedical personal identity.

Mundane identity: Already when we came to the neonatal clinic, a couple of days after the delivery, our little girl had, in our eyes, acquired a fairly stable identity: the way she opened her eyes, her crying, sleeping, waking, eating and shitting ‘habits’, the way she had a hickup after eating, body surface temperature, etc. We would immediately have found out if she had been replaced with another baby of the same physiognomy and size.

The ‘biomedical identity’ is quite different, however. A human individual can also be thought of in terms of the many kinds of invisible vital measurement parameters that clinical medicine has made use of throughout the 20th century — from simple blood grouping and blood cell counts to the hundreds of biomarkers and physiological processes that can be measured in contemporary diagnostic laboratories. For example, in Picturing Personhood: Brain Scans and Biomedical Identity (2003), anthropologist Joseph Dumit showed how PET scan images are incorporated into doctors’ and patients’ understandings of the personal identity of the scanned individual.

So here was our newborn — seemingly well and happy in spite of her infected thumb, with her quite unique hickup and other features of her budding mundane personal identity in place — laying asleep with a measuring device taped onto her left foot.  On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.

On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.

Watching the screens in the ‘control room’, we could also see how her biomedical identity differed from the other infants. We were not allowed to visit the others — so we couldn’t construct the mundane identities of the others, except for occasional cryings here and there. The other infants had biomedical identities only.

All this made me think about how my daughter will experience the world when she in turn becomes a mother thirty years from now? In a near future when nano-sized diagnostic devices may be able to monitor 30, 50 or 100 biochemical and physiological parameters, when the data can be sent via new generations of miniaturized internal RFID transponders to her mobile ‘phone’ (or whatever such a thing will then be called), which in turn will transmit continuous vital data from her and everybody else to the transnational population bio-control center in Beijing.

Will she then just take for granted that a personal identity equals the sum of biological parameters and that the difference between ‘you’ and ‘me’ primarily resides on the screen in the bio-control center? I ask because I sort of care for her future, and because this possible conjuntion between emerging technologies, biopolitics and surveillance technology may be closer than we think (see also www.googlepopulation.cn).

Same procedure as last year? Yes, same procedure as every year! In other words, also this year Medical Museion participates in the Night of Culture (Kulturnatten) in Copenhagen, when hundreds of museums, galleries and other institutions in the inner city area are open from 6pm until midnight.

Same procedure as last year? Yes, same procedure as every year! In other words, also this year Medical Museion participates in the Night of Culture (Kulturnatten) in Copenhagen, when hundreds of museums, galleries and other institutions in the inner city area are open from 6pm until midnight.

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’.

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’. If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient.

If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient. On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.

On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.

Yes, if we shall believe the

Yes, if we shall believe the  “Part of a more general ‘spatial turn’” (i.e.,

“Part of a more general ‘spatial turn’” (i.e.,  The

The  The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators,

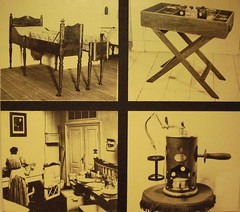

The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators,  The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements.

The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements.