We’ve just opened our new exhibition, ‘The Chemistry of Life’, in our satellite exhibition area in the main building of the Faculty of Health Sciences (the Panum Building). For the record, here’s the talk I gave at the opening (for images from the opening, see here):

We’ve just opened our new exhibition, ‘The Chemistry of Life’, in our satellite exhibition area in the main building of the Faculty of Health Sciences (the Panum Building). For the record, here’s the talk I gave at the opening (for images from the opening, see here):

The occasion for Medical Museion’s new exhibition, ’The Chemistry of Life’, is the new Center for Basic Metabolic Research here at the Faculty of Health Sciences.

But the Center is only the occasion. What you will see in a few minutes is not an exhibition about any of the aspects of metabolism—diabetes, or obesity, or insulin resistance, or the metabolic syndrome—which the Center will be focus on in the years to come.

Instead, we have chosen to take a look at the long research tradition that the Center has grown out of. We are presenting four snapshots from the long and complex history of metabolic research. Each snapshot represents a constellation of people, things and ideas from a significant phase in this history. And to make it easier for you to differentiate between these four constellations, we have given them different colours: green, orange, blue and lilac.

We begin in Italy back in the early 17th century, where we examplify an early approach to metabolism with Santorio Santorio, a medical doctor in Padua, who made his way into the hall of fame of medical history, because he applied Galileo Galilei’s quantitative principle to physiology: “Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not”. For example, Santorio famously put himself in a chair balance to measure how his body lost weight even when no excretions could be registered.

We begin in Italy back in the early 17th century, where we examplify an early approach to metabolism with Santorio Santorio, a medical doctor in Padua, who made his way into the hall of fame of medical history, because he applied Galileo Galilei’s quantitative principle to physiology: “Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not”. For example, Santorio famously put himself in a chair balance to measure how his body lost weight even when no excretions could be registered.

Unfortunately, our tight budget hasn’t allowed us pay the insurance costs for borrowing original 17th century instruments from our Italian science museum colleagues. So to illustrate Santorio’s quantitative spirit, we had to find objects—balances, pulse meters, and thermometers—from later periods, in our own collections.

Then we make a leap forward, more than 200 years in time, to Copenhagen in the mid-19th century, when Peter Ludvig Panum laid the foundation of the strong Danish tradition for experimental physiology. Medical Museion has a wonderful collection of instruments used by mid- and late century Danish physiologists—it’s every historical instrument collector’s dream-come-true (and one of the reasons why we soon need to strengthen the fire security around these internationally unique collections even more).

Then we make a leap forward, more than 200 years in time, to Copenhagen in the mid-19th century, when Peter Ludvig Panum laid the foundation of the strong Danish tradition for experimental physiology. Medical Museion has a wonderful collection of instruments used by mid- and late century Danish physiologists—it’s every historical instrument collector’s dream-come-true (and one of the reasons why we soon need to strengthen the fire security around these internationally unique collections even more).

Again a leap, now another 50 years, to the Nobel winning research done by August Krogh and by his wife Marie Krogh in the first decades of the 20th century. August Krogh was a pioneer in the study of whole-body gas exchange and also a very prolific inventor of instruments. We actually have quite a few of these in Medical Museion’s collections, and we are very proud to be able to display some of these in this show, for example this balance spirometer, which Marie Krogh used in her clinical studies of basic metabolic rates:

Again a leap, now another 50 years, to the Nobel winning research done by August Krogh and by his wife Marie Krogh in the first decades of the 20th century. August Krogh was a pioneer in the study of whole-body gas exchange and also a very prolific inventor of instruments. We actually have quite a few of these in Medical Museion’s collections, and we are very proud to be able to display some of these in this show, for example this balance spirometer, which Marie Krogh used in her clinical studies of basic metabolic rates:

And finally, the last leap. In the fourth (lilac) theme we are entering a territory, which historians so far have largely stayed away from, namely contemporary research in molecular metabolism, genomic research, genome-wide association studies and so forth. We are shaky grounds here, because we don’t have the historical distance to the events.  As historians, we don’t really know yet which the significant breakthroughs have been. We don’t know who the Santorios, the Panums and the Kroghs of contemporary molecular metabolic studies are. For us, these people are still Nomina Nescimus (unknown names), and therefore we need your help to identify them and their contributions. I’ll get back to this in a few minutes.

As historians, we don’t really know yet which the significant breakthroughs have been. We don’t know who the Santorios, the Panums and the Kroghs of contemporary molecular metabolic studies are. For us, these people are still Nomina Nescimus (unknown names), and therefore we need your help to identify them and their contributions. I’ll get back to this in a few minutes.

Like all serious science exhibitions, ‘The Chemistry of Life’ is actually research-based. The two main curators—postdoc Adam Bencard and former consultant Sven Erik Hansen—have read quite a lot from the 19th and 20th physiological literature, and spent months looking at objects and images in our collection. Every word in this exhibition has been chosen with great care, from both medical, historical and philosophical points of view. In one sense then (in terms of the making of it) this is a research-based exhibition. But in another sense (in terms of the way it presents itself to the spectator), we think of it rather as a work of art.

Not just as a display of works of art, like this painting by David Goodsell at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla (which we commissioned from him specifically for this occasion):

We also see the exhibition itself as an art installation. By taking things out of their laboratory context and placing them in this new setting, they are transformed, from being scientific objects to becoming art objects. Taken as a whole they constitute a joint science and art exhibition. Not sci-art, but joint science and art.

By thinking exhibitions about science in terms of art installations and art exhibitions, Medical Museion in joining a growing trend within the world of museums of science, technology and medicine. Most of these mueums still understand themselves as informal learning institutions. They want to make people, including students, interested in science by teaching the history of science.

But what we at Medical Museion – and some of our good colleagues, like the Wellcome Collection in London – are increasingly trying to do, is to work out an alternative to this didactical understanding of what science museums and their exhibitions are good for.

Instead of making exhibitions that teach and explain science and the history of science, we rather want to engage the audience to reflect. Not because we don’t believe in the importance of learning about science and its history. But because we believe learning is done much better by other means—in teaching laboratories, by reading books, or through the internet—than by means of exhibitions. What the exhibition medium is good at, is to engage people’s aesthetic sensibilities. By whetting the appetite of the senses, exhibitions can evoke a more subjective, personal-based and thereby deeper reflection about science, its history and its future.

Back to the fourth theme (the lilac one) about today’s metabolic research. Like a growing number of museums—but not necessarily the same museums who think in terms of art installations—we believe that exhibition making has to be built on participation. Of course, museum professionals take a lot of pride in trying to produce perfectly researched and perfectly designed exhibitions (and we at Medical Museion are no exception). Yet, we must realize that such pride in perfection does not necessarily result in engaged visitors.

And for that reason, some museums around the world have begun to ask their visitors and peers to contribute more actively to the museum functions. In analogy to social web media, some museums are now thinking in terms of the ‘participatory museum’ (‘museum 2.0’).

With respect to collections, the idea of a participatory museum is not a particularly new one. For example, our museum here in Copenhagen has been participatory since its foundation in 1907, in the sense that most objects in our rich collections have been donated by medical doctors. Also for ‘The Chemistry of Life’ we have collected from scientists and medical device companies.

With respect to exhibitions, however, few science museums have so far thought these in terms of participation. But this is about change. ‘The Chemistry of Life’ is an experiment in participatory exhibition making.  Like software, which is never really finished, but is improved by the responses from the customers, we have thought it—especially the fourth chapter on ‘Molecular Metabolism—as a ‘beta version’.

Like software, which is never really finished, but is improved by the responses from the customers, we have thought it—especially the fourth chapter on ‘Molecular Metabolism—as a ‘beta version’.

By labeling it ‘beta’ we are inviting all faculty, technical staff and students at the University of Copenhagen to help us developing ‘The Chemistry of Life’. Instead of us telling you what is going on in metabolic research, we want you to educate us. For example, we will invite scientists, who have been part of the development of the last decades of metabolic research to a seminar, where we will ask them to tell us what they think are the most important idas, events and people in the history of the field. They may not agree among themselves, but we will nevertheless be more knowledgeable after the seminar.

We are also planning an ‘object’-day, where we invite scientists and medical doctors from the entire region to bring images of their favourite objects, or (even better) bring in the objects themselves. The result should hopefully be that, at the official opening of the Center for Basic Metabolic Research in the spring, we can show a revised version of ‘The Chemistry of Life’, especially a much more interesting and thought-provoking fourth theme.

The notion of ‘beta’ also indicates how Medical Museion will work together with the Center in the years to come. We are right now making plans for a series of exhibitions about diabetes, obesity and the new metabolic syndrome—to be shown both in Denmark and abroad, both to professionals and to the general public—and we very much want to do this in close co-operation with scientists and students here at the Faculty.

Before I give the word back to the Dean, I want to express my gratitude to the individuals, institutions and companies, who have made this exhibition possible:

- Arne Astrup, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Copenhagen

- Lene Berlick, Illumina, Little Chesterford

- Jan Fahrenkrug, Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen

- Pia Gåsland, Agilent Technologies, Hørsholm

- David Goodsell, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla

- Jens Juul Holst, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen

- Anders Johnsen, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- John Gargul Lind, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Copenhagen

- Oluf Borbye Pedersen, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Copenhagen

- Jens F. Rehfeldt, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Thue Schwartz, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen

- Anna Smith, The Wellcome Collection, London

- Mao Tanabe, Kanehisa Laboratory, Kyoto

and to the Novo Nordisk Foundation for its generous economic support.

And finally the exhibition team. If this was a scientific article, the team would be presented somewhat like this:

Bencard A, Hansen SE, Thorsted M, Madsen H, Gerdes N, Vilstrup-Møller NC, Meyer I, Pedersen BV, Soderqvist T. The chemistry of life: four chapters in the history of metabolic research. Panum Building 2010; 4:1

Or more conventionally like this:

- Curators: Adam Bencard, Sven Erik Hansen

- Collection staff: Nanna Gerdes, Niels Christian Vilstrup-Møller, Ion Meyer

- Architect: Mikael Thorsted

- Graphic design: Helle Madsen

- Graphic production: Exponent Stougaard A/S

- Producers: Bente Vinge Pedersen, Thomas Söderqvist

Here we are:

Speaking for all of us: I hope you will enjoy this appetizer to a future co-operative science communication programme here at the Faculty which shall engage both scientists and the public in what has been going on in metabolic research in the past, what is going on today, and what we might expect from the future.

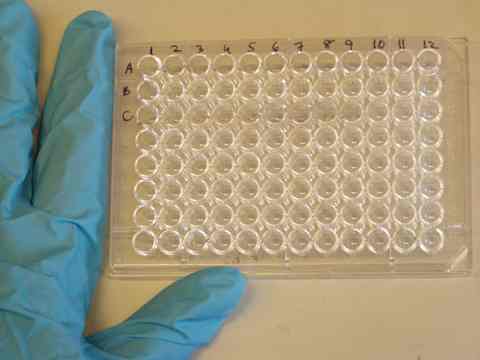

One of my favourite objects for acquisition and display from the world of biomedical and clinical laboratories is the microplate (microtiter plate, microwell plate).

One of my favourite objects for acquisition and display from the world of biomedical and clinical laboratories is the microplate (microtiter plate, microwell plate). What about the history of the microplate? Professional historians of medicine and/or technology haven’t paid much attention to the unassuming plastic lab device. After a few minutes on the web, however, I found out that the earliest microplate seems to have been constructed by the Hungarian medical microbiologist Gyula Takácsy (1914-1980). The Hungarian National Center for Epidemiology writes on their website that:

What about the history of the microplate? Professional historians of medicine and/or technology haven’t paid much attention to the unassuming plastic lab device. After a few minutes on the web, however, I found out that the earliest microplate seems to have been constructed by the Hungarian medical microbiologist Gyula Takácsy (1914-1980). The Hungarian National Center for Epidemiology writes on their website that:

We’ve just opened our new exhibition, ‘The Chemistry of Life’, in our satellite exhibition area in the main building of the Faculty of Health Sciences (the Panum Building). For the record, here’s the talk I gave at the opening (for images from the opening, see

We’ve just opened our new exhibition, ‘The Chemistry of Life’, in our satellite exhibition area in the main building of the Faculty of Health Sciences (the Panum Building). For the record, here’s the talk I gave at the opening (for images from the opening, see  We begin in Italy back in the early 17th century, where we examplify an early approach to metabolism with Santorio Santorio, a medical doctor in Padua, who made his way into the hall of fame of medical history, because he applied Galileo Galilei’s quantitative principle to physiology: “Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not”. For example, Santorio famously put himself in a chair balance to measure how his body lost weight even when no excretions could be registered.

We begin in Italy back in the early 17th century, where we examplify an early approach to metabolism with Santorio Santorio, a medical doctor in Padua, who made his way into the hall of fame of medical history, because he applied Galileo Galilei’s quantitative principle to physiology: “Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not”. For example, Santorio famously put himself in a chair balance to measure how his body lost weight even when no excretions could be registered. Then we make a leap forward, more than 200 years in time, to Copenhagen in the mid-19th century, when Peter Ludvig Panum laid the foundation of the strong Danish tradition for experimental physiology. Medical Museion has a wonderful collection of instruments used by mid- and late century Danish physiologists—it’s every historical instrument collector’s dream-come-true (and one of the reasons why we soon need to strengthen the fire security around these internationally unique collections even more).

Then we make a leap forward, more than 200 years in time, to Copenhagen in the mid-19th century, when Peter Ludvig Panum laid the foundation of the strong Danish tradition for experimental physiology. Medical Museion has a wonderful collection of instruments used by mid- and late century Danish physiologists—it’s every historical instrument collector’s dream-come-true (and one of the reasons why we soon need to strengthen the fire security around these internationally unique collections even more). Again a leap, now another 50 years, to the Nobel winning research done by August Krogh and by his wife Marie Krogh in the first decades of the 20th century. August Krogh was a pioneer in the study of whole-body gas exchange and also a very prolific inventor of instruments. We actually have quite a few of these in Medical Museion’s collections, and we are very proud to be able to display some of these in this show, for example this balance spirometer, which Marie Krogh used in her clinical studies of basic metabolic rates:

Again a leap, now another 50 years, to the Nobel winning research done by August Krogh and by his wife Marie Krogh in the first decades of the 20th century. August Krogh was a pioneer in the study of whole-body gas exchange and also a very prolific inventor of instruments. We actually have quite a few of these in Medical Museion’s collections, and we are very proud to be able to display some of these in this show, for example this balance spirometer, which Marie Krogh used in her clinical studies of basic metabolic rates:

As historians, we don’t really know yet which the significant breakthroughs have been. We don’t know who the Santorios, the Panums and the Kroghs of contemporary molecular metabolic studies are. For us, these people are still Nomina Nescimus (unknown names), and therefore we need your help to identify them and their contributions. I’ll get back to this in a few minutes.

As historians, we don’t really know yet which the significant breakthroughs have been. We don’t know who the Santorios, the Panums and the Kroghs of contemporary molecular metabolic studies are. For us, these people are still Nomina Nescimus (unknown names), and therefore we need your help to identify them and their contributions. I’ll get back to this in a few minutes.

Like software, which is never really finished, but is improved by the responses from the customers, we have thought it—especially the fourth chapter on ‘Molecular Metabolism—as a ‘beta version’.

Like software, which is never really finished, but is improved by the responses from the customers, we have thought it—especially the fourth chapter on ‘Molecular Metabolism—as a ‘beta version’.

Last winter, I was invited to contribute to a thematic issue (edited by

Last winter, I was invited to contribute to a thematic issue (edited by