Good news for all friends of sound artist Jacob Kirkegaard (see earlier post here), and for all fans of the Museum of Jurassic Technology (MJT) in Culver City — Jacob has just given a sold-out performance of his inner-ear sound work ‘Labyrinthitis’ in the MJT’s Tula Tea Room. Read Jacob’s impressions from the MJT here. The Athanasius Kircher connection is obvious! Not only does the MJT have a permanent exhibition about “the last Renaissance man”, he has also been a great inspiration to Jacob’s sound works. Another example of how Renaissance and early modern culture connects with contemporary concerns.

The aim of the National Pathology Week in the UK, 3-9 November is to highlight pathology’s impact on the health of the population through a range of “fun, free and exciting” events. One of the more fun- and exciting-looking ones from a medical museum point of view is ‘Autopsy: the ultimate surgical operation’, which will take place at the Hunterian Museum in London on 8 November, between noon and 2pm.

We all know what surgeons do and most of us have had an operation or know someone who has. But have you ever wondered about the last surgery many people have –– an autopsy? Is it just as it’s shown on TV or is there more to it? This is a chance for you to meet the people who perform autopsies and find out how they help doctors understand more about disease, as well as how how to treat living patients.

Sounds like a good complement to the obligatory autopsy scenes in tv crime and mystery series (when did you last see a crime series which did not contain an autopsy room scene, however short?). See the flyer here. For further information or to book a place, write to ruth.semple@rcpath.org.

A rapidly increasing number of scientists and scholars are learning about the advantages of using the blog medium for both internal and external research communication — see for example Batts, Anthis and Smith’s recent paper “Advancing science through conversations: bridging the gap between blogs and the academy” in Public Library of Science: Biology (vol. 6, Sept., e240 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060240) (discussed in an earlier post here).

But it can surely be pretty demanding to keep up a quality blog. As Stanford bioinformatician Russ Altman writes under the heading “Blogs are hard!” on his excellent Building Confidence blog (about biomedical informatics, genetics, medicine, and bioengineering):

Well, maybe you all know this, but I am having a heck of a time coming up with material that is relevant and (hopefully) interesting for this blog. These difficulties are occurring despite help from my blog angel (she knows who she is) who is constantly feeding me excellent ideas. Why are blogs hard?

- Things are busy and you need to take out time to be a little reflective about stuff. That’s hard when you are just running and running all day.

- In order to opine, you need to know what you are talking about. That usually requires doing some homework.

- It is difficult to formulate ideas alone. Almost everything I do is as part of a team, and this is a much better way (generally speaking) to draw conclusions or make decisions. If I really wanted excellent blog items, I think I should work with a team to formulate good thoughts, debate them and then present them. But I’m not sure that’s part of the blog culture, which is marked by rugged individualism

OK, that’s my thoughts about why I have blog block. I will get going again soon. Blog angel has sent some great ideas, and I just need to ponder them, form opinions, and commit them to screen.

A sobering voice amidst all the exhausting enthusiasm that’s swirling around the science blogging multitude. Searched for “blog block“, and got a staggering 8,331 hits.

(thanks to Deepak for the tip about Russ Altman’s post)

Same procedure as last year? Yes, same procedure as every year! In other words, also this year Medical Museion participates in the Night of Culture (Kulturnatten) in Copenhagen, when hundreds of museums, galleries and other institutions in the inner city area are open from 6pm until midnight.

Same procedure as last year? Yes, same procedure as every year! In other words, also this year Medical Museion participates in the Night of Culture (Kulturnatten) in Copenhagen, when hundreds of museums, galleries and other institutions in the inner city area are open from 6pm until midnight.

During the last eight years, we’ve had between 2,500 and 3,000 visitors passing through the doors in six hours (usually peaks at 9pm). Also this year our staff will be standing prepared all over the museum building to answer questions about the collections and exhibitions. For example, take this opportunity to see our critically acclaimed temporary exhibition Oldetopia: Age and Ageing which closes in mid-December.

A new feature this year are choir performances in the old anatomical theatre: ”Bastionens Kor” directed by Cæcilia Glode and ”Vokalgruppen Kolorit” led by Niels Græsholm. You can also have your lung capacity measured by physicians and nurses from the Danish Lung Society (Danmarks Lungeforening).

To get access to Medical Museion and all the other events during the Night of Culture in Copenhagen you will need a special pass, which can be bought here for 75 DKK.

(for a Danish version of this post, see our new Danish blog, Museionblog).

As I wrote in a previous post, our little newborn was transferred from the maternity ward to the neonatal clinic to keep her under observation for a couple of days (because of an infected thumb; never neglect small wounds in small children, they have a weak immune system!).

To keep my paternal anxiety under control, I began to look around and take some photographs of this peculiar, high-tech medical space. And what especially triggered my curiosity (besides the mysterious use of old historical images, see earlier post) was the monitoring system.

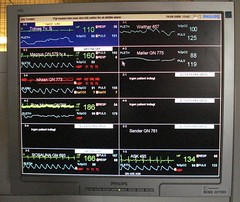

‘Our’ ward team cares for twelwe patients, from very prematurely born (down to 21 weeks!) to newborns with all kinds of medical conditions, most of them much more serious than our infant’s. Each is kept under surveillance with respect to heart beat frequence, oxygen saturation level, blood pressure, and so forth.

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’.

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’.

If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient.

If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient.

What intrigued me wasn’t the system as such, however — I guess such monitoring platforms (in this case Philips IntelliVue MP90) are pretty much standard equipment in most neonatal wards and emergency medicine rooms in the rich parts of the world — but rather how the system’s visualization of the monitored vital data began to change my conception of our newborn’s identity. Within a few hours, I went from thinking about her in terms of mundane identity to constructing an entirely new, biomedical personal identity.

Mundane identity: Already when we came to the neonatal clinic, a couple of days after the delivery, our little girl had, in our eyes, acquired a fairly stable identity: the way she opened her eyes, her crying, sleeping, waking, eating and shitting ‘habits’, the way she had a hickup after eating, body surface temperature, etc. We would immediately have found out if she had been replaced with another baby of the same physiognomy and size.

The ‘biomedical identity’ is quite different, however. A human individual can also be thought of in terms of the many kinds of invisible vital measurement parameters that clinical medicine has made use of throughout the 20th century — from simple blood grouping and blood cell counts to the hundreds of biomarkers and physiological processes that can be measured in contemporary diagnostic laboratories. For example, in Picturing Personhood: Brain Scans and Biomedical Identity (2003), anthropologist Joseph Dumit showed how PET scan images are incorporated into doctors’ and patients’ understandings of the personal identity of the scanned individual.

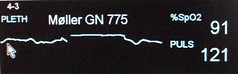

So here was our newborn — seemingly well and happy in spite of her infected thumb, with her quite unique hickup and other features of her budding mundane personal identity in place — laying asleep with a measuring device taped onto her left foot.  On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.

On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.

Watching the screens in the ‘control room’, we could also see how her biomedical identity differed from the other infants. We were not allowed to visit the others — so we couldn’t construct the mundane identities of the others, except for occasional cryings here and there. The other infants had biomedical identities only.

All this made me think about how my daughter will experience the world when she in turn becomes a mother thirty years from now? In a near future when nano-sized diagnostic devices may be able to monitor 30, 50 or 100 biochemical and physiological parameters, when the data can be sent via new generations of miniaturized internal RFID transponders to her mobile ‘phone’ (or whatever such a thing will then be called), which in turn will transmit continuous vital data from her and everybody else to the transnational population bio-control center in Beijing.

Will she then just take for granted that a personal identity equals the sum of biological parameters and that the difference between ‘you’ and ‘me’ primarily resides on the screen in the bio-control center? I ask because I sort of care for her future, and because this possible conjuntion between emerging technologies, biopolitics and surveillance technology may be closer than we think (see also www.googlepopulation.cn).

I’m amazed nobody has thought of this before, viz., making a guessing contest about who will be awarded the Nobel prizes. But apparently Medgadget is the first to do so.

The rules of their Guess-A-Nobel contest are easy: post your guess which scientist(s) or discovery(ies) will be awarded in their comment section here. You don’t need to motivate it further. You can take a guess at the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and the prizes on Physics and Chemistry, respectively.

Unfortunately, Medgadget isn’t as well-endowed as the Nobel Foundation, so there are no large Swedish krona awards ín wait. The winner(s) each get an iPod nano, however, and the reputation for being good at Nobel divination, of course 🙂

It’s a good idea — but has this really not been done before? Upplands-Bro county library (in Sweden) has a guess-a-literature-prize contest where the winner gets free entrance to the Nobel lecture. Any others?

Added 29 Sept 1:30pm: My good collegaue Svante Lindqvist at the Nobel Museum in Stockholm points out in a mail that the British betting and gambling company Ladbrokes have accepted bets for Nobel Prize winners for years (but that’s something different than a public contest, of course)

Universities aren’t precisely drawback-free zones — yet I’ve been thinking about how privileged university-based blogs are when I see some of our science blogging peers who (have to, or feel they have to?) fill their blogs with banner ads and Google Adsense links. A university financed blog doesn’t have to think about blog ad networks, average payment per blog post, pay-per-clicks, pay-for-post marketing strategies, banner advertising spending, or speculate about how to provide better value for advertisers. And we don’t have to meet with target audience advertising agencies and their ilk. That’s a privilege.

Yes, if we shall believe the Aarhus Network for Science, Technology and Medicine Studies which is hosting a one-day conference in Aarhus, Denmark, 23 October, under the heading ‘Challenging hyperprofessionalism: The intradisciplinarity of science, technology and medicine studies’.

Yes, if we shall believe the Aarhus Network for Science, Technology and Medicine Studies which is hosting a one-day conference in Aarhus, Denmark, 23 October, under the heading ‘Challenging hyperprofessionalism: The intradisciplinarity of science, technology and medicine studies’.

To present “the richness of what is going on across the disciplines”, the organisers invite “research based papers or posters, including work-in-progress, broadly within science, technology and medicine studies”, especially contributions that address the intradisciplinarity issue.

Each paper will only be allotted 20 minutes for presentation and questions (not much time, really!). Titles and 100 word abstracts are due 8 October (send to idenklk@hum.au.dk). Slightly more info here.

Following two succesful earlier meetings (in Stockholm in 2006 and in Gothenburg 2007), the Swedish medical history network organizes its third conference, again in Stockholm, on Thursday 29 January 2009. The main item on the meeting agenda is the planned project for writing the history of the Karolinska Institute, founded in 1810, and today one of the world’s leading medical research universities. As the project involves up to ten Swedish medical historians in 2008 and 2009, it will probably dominate the meeting, but the organizers promise that there will be plenty of time for presentation of other current research projects as well. Conference language is Swedish, but you don’t need a Swedish passport to attend. For inquiries, contact Roger Qvarsell, roger.qvarsell@isak.liu.se, http://www.isak.liu.se/temaq/rq/presentation.

Last year, this blog participated in an online survey of medical blogs undertaken by Ivor Kovic, Ileana Lulic and Gordana Brumini at Rijeka University School of Medicine in Croatia. Now they have published the results in a paper titled “Examining the medical blogosphere: an online survey of medical bloggers” in the last issue of Journal of Medical Internet Research, one of the top-ranked journals in the health informatics.

Among the results:

- 6 out of 10 medical bloggers are men (more balanced than I thought)

- 1 out of 3 is a physician (that’s pretty much — will probably grow)

- over 50% have published a scientific paper (impressive!)

- 1 out of 4 medical bloggers prefer to be anonymous (bad habit!)

- 60% of the respondents spend 20 hours or more per week on the internet (not unsurprisingly)

In other words, the typical medical blogger is a male medical doctor with some scientific training who spends most of his spare-time on the internet. Not surprising, I guess 🙂

You can also see a summary of the report in this slide show presentation.