Last night, I had a couple of beers with an American bioartist and some of his friends. I have always been somewhat sceptical about what is going on in so called genomic art, and after my first pint of Herslev Pale Ale, I suddenly found myself saying: ‘Genomic art is so much last year’.

My guest protested vigorously, probably because some of his own recent work can be designated ‘genomic art’. How could I mean that? Before he had the chance to refer to the many great works that have been produced in the last 10 years, I continued my argument.

Genomic art grew up in the wake of the immense public interest in the human genome project in the 1990s and early 2000s. It was an oblique response to the importance attached to the genome among scientists, funding agencies, pharma companies, the media, and social critics. Genomic art was fuelled in a tension between the bioscience establishment and a critical political and intellectual movement.

Now, the heat of genomics is over. What is now discussed in the research world — in private/public laboratories and in the board rooms of funding agencies, Big Pharma, and biotech companies — is proteomics. Largely because the design of specific, targeted protein molecules and knowledge about their interactions in the cell is supposed to have great potentials for future drug production.

Genomic art will continue to be produced, of course, but it is no longer fuelled by the political tension of the 1990s. It now lives a life of its own, less driven by political and critical discussions. However, there is so far not much interesting protein art to speak of.

My bioartist friend didn’t agree. Maybe I was right with respect to the changes taking place in the research and industrial world, but he thought I attached too much significance to this change, because proteins are the product of the transcription and translation of DNA/RNA and therefore play a secondary role on life — and, as a consequence, for critical bioartists.

To which I responded that in spite of this ‘secondary role’ of proteins, artists interested in materiality (which most bioartists are) should nevertheless pay more attention to them than to DNA/RNA, because the material substrate of the cell and body functions lies precisely in the interaction between proteins, not in the information that has coded for them.

Again disagreement: Nucleic acids are not just code, they are material too. Right you are, I said, but the material presence and direct material consequences of nucleic acids in the body is small compared to the material presence and consequences of proteins, so we can as well forget about it.

Unfortunately, our discussion ended there, because I had to go home. If I could have continued it, however, I would have said that I’m of course not suggesting that the future direction of bioart should be determined by shifting research focuses in the biosciences, or that the strong material presence of this or that molecular species should be a reason for an artist to pay attention to it. That is not how bioart, or any other art form, works.

But the fact that my bioartist friend and I got into such a heated discussion about genomic versus proteomic art is nevertheless interesting, I think.

(Dictated through my Dragon speech recognition software, therefore, alas, no links or images today)

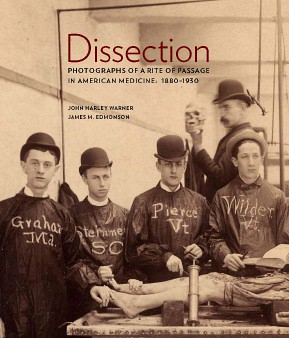

We are usually covering contemporary biomedicine on display on this blog, but sometimes older stuff gets its way into this column as well.

We are usually covering contemporary biomedicine on display on this blog, but sometimes older stuff gets its way into this column as well.