Here’s the introduction to a talk titled ‘Cultures of Meaning and Cultures of Presence: The use of material objects in the history of science, medicine and technology’ that I gave at the Museo da Ciencia da Universidade Lisboa two weeks ago (see flyer here and resumé in Portuguese here); the images are from the web and for general illustration only:

Before I went into history of science and medicine (and then medical museology), I took a Masters in chemistry, zoology and historical geology (major).

Today, when I look back on my student years at a distance, I realise these disciplines were very much about the handling of tangible material stuff, involving all five senses. Chemistry, zoology and geology students were not just thinking about or viewing the world — we were also listening to it, smelling, tasting and touching it.

Chemistry was (at least when I was a student) about reactions between palpable chemical substances; it involved handling glassware and physical measuring instruments; lots of stuff was pretty smelly, we were constantly exposed to the sounds of boiling liquids and suction pumps; experiencing glowing heat and freezing cold were parts of the daily experience in the lab.

Zoology was very material too.  We observed birds in the field, collected insects and marine animals, killed and dissected them, made microscopical thin sections and grinded organs down to cells and molecular extracts. Animal beings weren’t just genomic code — they were sometimes smelly, often noisy, always tangible.

We observed birds in the field, collected insects and marine animals, killed and dissected them, made microscopical thin sections and grinded organs down to cells and molecular extracts. Animal beings weren’t just genomic code — they were sometimes smelly, often noisy, always tangible.

Historical geology, finally, was about handling real stones, minerals and sediments with axes, spades, knives and brushes. We spent weeks in the field working outcrops and long hours in the lab afterwards, sorting out physical fossil specimens.

Historical geology, finally, was about handling real stones, minerals and sediments with axes, spades, knives and brushes. We spent weeks in the field working outcrops and long hours in the lab afterwards, sorting out physical fossil specimens.

After this undergraduate immersion in the material world of science, I started in a PhD-programme in biochemistry at Karolinska Institute. I collected blood from animals which I had killed with my own hands, stood in the lab’s cold room for hours purifying blood proteins, degraded them with chemicals, separated the fragments in chromatography columns which I had packed myself, and then handled different kinds of lab glassware and measuring instruments to elucidate their amino acid sequences. The protein laboratory was a very physical place with lots of machines and chemicals — and again it involved all the senses.

So science was a very material and sensory practice. And if I hadn’t been confronted with its potentially deadly consequences — one day I swallowed a radioactively labelled substance by mistake (always remember to use a pipette bulb!) — I might have become a real scientist.

Instead, I left science to pursue my high school philosophical interests — what is classification? what’s a concept? what’s the relation between a name, a concept and reality? what’s stuff made of? (all classical epistemological and ontological questions) — took courses in philosophy of science and history of ideas, and then started a new PhD project on the historiography of 20th century science, more precisely the historiography of ecology.

The history and philosophy of science was, I realise now, an entirely different experience. Instead of manipulating and being surrounded by material objects, I found myself sitting at a desk, reading old scientific papers and books. I visited archives to look for handwritten documents and interviewed elderly scientists about their past.

In other words, history and philosophy of science was a world of words and texts (written or spoken). There were actually no material objects in my new disciplinary identity, except for the pulp the texts were written on.

Shifting from PhD-studies of the historiography of ecology to postdoc studies of the historiography of immunology, didn’t change my textual practice. True, I sometimes met practicing immunologists in conferences about the history and philosophy of immunology, but these meetings still revolved around texts and words. People read conference papers based on readings of other texts. Again — text, text, text.

My own research practice was also totally text-based. I spent eight years of my life going through the huge archive of a contemporary immunologist, and spent hundreds of hours talking with him. And when I visited his former colleagues to interview them, we talked and inspected documents and photographs together. We never went to their labs to handle a piece of immunological lab equipment together.

It was as if the material and sensory world of science which I had been so thoroughly immersed in on a daily basis when I was a student totally disappeared when I entered history and philosophy of science. From a world of stuff, smells, sounds, tastes and manual touch I had stepped into a world of disembodied text.

What is most remarkable, now when I look back on it, is that I wasn’t at all aware of the gulf that separated the material and sensuous world of science, and the textual and disembodied world of history and philosophy of science. It was as if I had lost the ability to experience the material and sensory qualities of the laboratory, as if I saw the world of science through the textual spectacles of history and philosophy of science. To the extent that when, occasionally, I visited laboratories, I only ‘saw’ papers, inscriptions and documents, maybe a few images here and there.

[..]

(thanks to Martha Lourenco at the Museu da Ciencia da Universidade Lisboa for inviting me to give the talk — this post contains the introduction only, the rest needs revision before being put online).

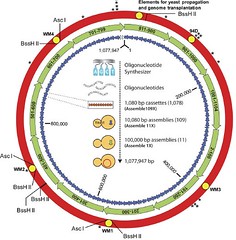

It’s not really synthetic life yet— it’s ‘just’ a synthetic genome, which has been designed in the computer, assembled from chemically synthesised oligonucelotides, and then put into a recipient cell, where the new synthetic genome took over control, thereby creating a new Mycoplasma species. Nevertheless — it’s pretty mindblowing.

It’s not really synthetic life yet— it’s ‘just’ a synthetic genome, which has been designed in the computer, assembled from chemically synthesised oligonucelotides, and then put into a recipient cell, where the new synthetic genome took over control, thereby creating a new Mycoplasma species. Nevertheless — it’s pretty mindblowing.

The 11th Universeum network meeting, titled ‘University Heritage: Present and Future’, will be held in the university museum of Uppsala University (Museum Gustavianum), on 17-20 June.

The 11th Universeum network meeting, titled ‘University Heritage: Present and Future’, will be held in the university museum of Uppsala University (Museum Gustavianum), on 17-20 June.