We’d love to see a long meeting series under the title “How Matter Matters: Objects, Artifacts and Materiality in X Studies”, where X could be alternatively Science Studies, History of Science, History of Medicine, History of Technology, etc. But first out was “Organization Studies” — to take place 16-18 June, 2011 on the Greek island Corfu. More info here.

Here is the preliminary programme for the workshop “Contemporary biomedical science and medical technology as a challenge to museums” (15th biannual meeting of the European Association of Museums for the History of Medical Sciences), to be held in Copenhagen, 16-18 September, 2010.

Here is the preliminary programme for the workshop “Contemporary biomedical science and medical technology as a challenge to museums” (15th biannual meeting of the European Association of Museums for the History of Medical Sciences), to be held in Copenhagen, 16-18 September, 2010.

The presentations below have been selected by the programme committee (Ken Arnold, Wellcome Collection, London; Robert Bud, Science Museum, London; Judy Chelnick, National Museum of American History, Washington DC; Mieneke te Hennepe, Boerhaave Museum, Leiden; and Thomas Söderqvist, Medical Museion, Copenhagen) in dialogue with the secretary of the EAMHMS (James Edmonson, Dittrick Museum, Cleveland).

Preliminary programme:

Sniff Andersen Nexø (Dept of History, University of Copenhagen):

TBA

Suzanne Anker (School of Visual Arts , New York):

“Inside/Out: Historical Specimens through a 21st Century Lens”

Kerstin Hulter Åsberg (Dept of Neuroscience, Uppsala University):

“Uppsala Biomedical Center: A Mirror and a Museum of Modern Medical History”

Yin Chung Au (Planning and Coordination Centre for Developing Science Communication Industry, National Science Council, Taiwan):

“Seeing is communicating: Possible roles of med-art in communicating contemporary scientific process with the general public in digital age

Adam Bencard (Medical Museion, University of Copenhagen):

“The molecular body on display”

Caitlin Berrigan (independent artist):

“Improvising Glycoproteins: A case study in artistic virology”

Danny Birchall (Wellcome Collection, London):

“Medical London and the photography of everyday medicine”

Silvia Casini (Observa – Science in Society, Venice):

“Curating the Biomedical Archive-fever”

Judy M. Chelnick (Division of Medicine and Science, National Museum of American History):

“The Challenges of Collecting Contemporary Medical Science and Technology at the Smithsonian Institution”

Roger Cooter (Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine, UCL) and Claudia Stein (Dept of History, University of Warwick):’

“Visual Things and Universal Meanings: Aids Posters, the Politics of Globalization, and History”

Nina Czegledy (Senior Fellow, KMDI, University of Toronto):’

“At the Intersection of Art and Medicine”

John Durant (MIT Museum):

“Prospects for International Collaboration in Collecting Contemporary Science and Technology”

Joanna Ebenstein (The Observatory, New York):

“The Private, Curious, and Niche Collection: What They can Teach Us”

Jim Edmonson (Dittrick Museum, Case Western Reserve University):

“Collection plan for endoscopy, documenting the period 1996-2010”

Jim Garretts (Thackray Museum, Leeds):

“Bringing William Astbury into the 21st Century: the Thackray Museum and the Astbury Centre for Structural Molecular Biology in partnership”

Victoria Höög (Dept of Philosophy and History of Science, University of Lund):

“The Optic Invasion of the Body. Naturalism as an Interface between Epistemic Standards in Biomedical Images and the Medical Museums”

Karen Ingham (School of Research and Postgraduate Studies, Swansea Metropolitan University):

“Medicine, Materiality and Museology: collaborations between art, medicine and the museum space”

Ramunas Kondratas (independent scholar; formerly Division of Medicine and Science, National Museum of American History):

“The Use of New Media in Medical History Museums”

Lucy Lyons (Medical Museion, University of Copenhagen):

“What am I looking at?”

Robert Martensen (Office of History & Museum, NIH):

“Integrating the Physical and the Virtual in Exhibitions, Archives, and Historical Research at the National Institutes of Health”

Stella Mason (independent scholar):

“Contemporary Medicine in Museums: What do our visitors think of our efforts?”

René Mornex and Wendy Atkinson (Hospices Civils de Lyon, Université Claude Bernard Lyon1):

“A large health museum in Lyon”

Jan Eric Olsén (Dept of History of Ideas, University of Lund):

“The displaced clinic: healthcare gadgets for home use”

Kim Sawchuk (Dept of Communication Studies, Concordia University):

“Bio-tourism into museums, galleries, and science centres”

Thomas Schnalke (Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum):

“Dissolving matters: the end of all medical museums’ games?”

Morten Skydsgaard (Steno Museum of the History of Science, Aarhus University):

“Boundaries of the Body and the Guest: Art as a facilitator in the exhibition The Incomplete Child”

Sébastien Soubiran (Jardin des Science, Université de Strasbourg):

“Which scientific world would we like to depict in a 21st century university museum?”

Yves Thomas (Polytech Nantes) and Catherine Cuenca (Université de Nantes and Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris):

”Multimedia contributions to contemporary medical museology”

Maie Toomsalu (Medical Collections, University of Tartu):

“Visitor studies at the Medical Collections of University of Tartu”

Henrik Treimo (Norsk Teknisk Museum, Oslo):

”Invisible World: Visualising the invisible parts of the body”

Alex Tyrell (Science Museum, London):

“New voices: involving your audience in content creation”

Nurin Veis (Museum Victoria, Melbourne):

“How do we tell the story of the cochlear implant?”

Final titles will be announced after the revised/extended abstracts have been submitted by Monday, 2 August.

The workshop starts Thursday, 16 September at noon and ends Saturday, 18 September at 5 pm.

Sessions will be held at Medical Museion and in the Danish Museum of Art and Design. The two meeting venues are situated close to each other in central Copenhagen.

The format of the workshop is informal. In order to focus on discussion and intellectual exchange, each accepted abstract will get a maximum of 8 (eight) minutes for oral presentation, followed by a longer discussion. Extended abstracts (2-5 pages) will be distributed to all registered participants in late August.

The workshop is open to registered participants only. Due to space limitations, we have to impose a first register/first serve policy for attendance.

For details about registration, bank transfer, hotel bookings, special needs, etc., see http://www.mm.ku.dk/sker/eamhms.aspx.

For inquiries about the academic programme, please contact the chair of the programme committee, professor Thomas Söderqvist, Medical Museion, ths@sund.ku.dk or +45 2875 3801.

For inquiries about the venue, accommodation, registration, bank transfer etc., please contact the secretary of the local organizing committee, Ms Anni Harris, anniha@sund.ku.dk or +45 3532 3800.

The workshop is organized by Medical Museion, University of Copenhagen (www.mm.ku.dk; www.corporeality.net/museion).

Soraya de Chadarevian (history of science, UCLA) came by this afternoon for a short and informal visit on her way to Lund and Gothenburg. Soraya went on a quick tour around the museum and afterwards we had a short chat in the meeting room — especially about collecting contemporary biomedicine.

Which made me think of Robert Anderson’s (former British Museum director) dictum that “acquisitioning is the life-blood of museums“. Not collections, not exhibitions, not research — but acquisitions. The active process of bringing new material stuff into museums is both the prerequisite of new interesting exhibitions and a source of new ideas and questions for research.

We used to rely on ‘garbage days’. Maybe it’s time to formulate a more comprehensive acquisitioning programme?

The social web is almost by definition centered around the hyperlink. One of the attractions with blogging is the possibility to sprinkle hyperlinks all over the text. Is there a drawback? Oh yes, says Nicholas Carr:

Sometimes, they’re big distractions — we click on a link, then another, then another, and pretty soon we’ve forgotten what we’d started out to do or to read. Other times, they’re tiny distractions, little textual gnats buzzing around your head. Even if you don’t click on a link, your eyes notice it, and your frontal cortex has to fire up a bunch of neurons to decide whether to click or not. You may not notice the little extra cognitive load placed on your brain, but it’s there and it matters. People who read hypertext comprehend and learn less, studies show, than those who read the same material in printed form. The more links in a piece of writing, the bigger the hit on comprehension.

I don’t know which studies Carr is referring to, because he doesn’t hyperlink — but intuitively I think he’s right.

He adds that one of the remedies may be to put the links at the end of the text (like end notes in an article).

Bioephemera is (temporarily?) closing down. As Jessica says, “everything is ephemeral – including bioephemera”. She has met “many wonderful fellow bloggers and faithful readers through the blog”, but keeping it going has become “a significant investment of time that I just don’t have … I need to refocus on work, life, and art”. Hopefully Jessica will return. Online life will be poorer without her thoughtful comments. Good luck with your work, life and art!

Here’s the introduction to a talk titled ‘Cultures of Meaning and Cultures of Presence: The use of material objects in the history of science, medicine and technology’ that I gave at the Museo da Ciencia da Universidade Lisboa two weeks ago (see flyer here and resumé in Portuguese here); the images are from the web and for general illustration only:

Before I went into history of science and medicine (and then medical museology), I took a Masters in chemistry, zoology and historical geology (major).

Today, when I look back on my student years at a distance, I realise these disciplines were very much about the handling of tangible material stuff, involving all five senses. Chemistry, zoology and geology students were not just thinking about or viewing the world — we were also listening to it, smelling, tasting and touching it.

Chemistry was (at least when I was a student) about reactions between palpable chemical substances; it involved handling glassware and physical measuring instruments; lots of stuff was pretty smelly, we were constantly exposed to the sounds of boiling liquids and suction pumps; experiencing glowing heat and freezing cold were parts of the daily experience in the lab.

Zoology was very material too.  We observed birds in the field, collected insects and marine animals, killed and dissected them, made microscopical thin sections and grinded organs down to cells and molecular extracts. Animal beings weren’t just genomic code — they were sometimes smelly, often noisy, always tangible.

We observed birds in the field, collected insects and marine animals, killed and dissected them, made microscopical thin sections and grinded organs down to cells and molecular extracts. Animal beings weren’t just genomic code — they were sometimes smelly, often noisy, always tangible.

Historical geology, finally, was about handling real stones, minerals and sediments with axes, spades, knives and brushes. We spent weeks in the field working outcrops and long hours in the lab afterwards, sorting out physical fossil specimens.

Historical geology, finally, was about handling real stones, minerals and sediments with axes, spades, knives and brushes. We spent weeks in the field working outcrops and long hours in the lab afterwards, sorting out physical fossil specimens.

After this undergraduate immersion in the material world of science, I started in a PhD-programme in biochemistry at Karolinska Institute. I collected blood from animals which I had killed with my own hands, stood in the lab’s cold room for hours purifying blood proteins, degraded them with chemicals, separated the fragments in chromatography columns which I had packed myself, and then handled different kinds of lab glassware and measuring instruments to elucidate their amino acid sequences. The protein laboratory was a very physical place with lots of machines and chemicals — and again it involved all the senses.

So science was a very material and sensory practice. And if I hadn’t been confronted with its potentially deadly consequences — one day I swallowed a radioactively labelled substance by mistake (always remember to use a pipette bulb!) — I might have become a real scientist.

Instead, I left science to pursue my high school philosophical interests — what is classification? what’s a concept? what’s the relation between a name, a concept and reality? what’s stuff made of? (all classical epistemological and ontological questions) — took courses in philosophy of science and history of ideas, and then started a new PhD project on the historiography of 20th century science, more precisely the historiography of ecology.

The history and philosophy of science was, I realise now, an entirely different experience. Instead of manipulating and being surrounded by material objects, I found myself sitting at a desk, reading old scientific papers and books. I visited archives to look for handwritten documents and interviewed elderly scientists about their past.

In other words, history and philosophy of science was a world of words and texts (written or spoken). There were actually no material objects in my new disciplinary identity, except for the pulp the texts were written on.

Shifting from PhD-studies of the historiography of ecology to postdoc studies of the historiography of immunology, didn’t change my textual practice. True, I sometimes met practicing immunologists in conferences about the history and philosophy of immunology, but these meetings still revolved around texts and words. People read conference papers based on readings of other texts. Again — text, text, text.

My own research practice was also totally text-based. I spent eight years of my life going through the huge archive of a contemporary immunologist, and spent hundreds of hours talking with him. And when I visited his former colleagues to interview them, we talked and inspected documents and photographs together. We never went to their labs to handle a piece of immunological lab equipment together.

It was as if the material and sensory world of science which I had been so thoroughly immersed in on a daily basis when I was a student totally disappeared when I entered history and philosophy of science. From a world of stuff, smells, sounds, tastes and manual touch I had stepped into a world of disembodied text.

What is most remarkable, now when I look back on it, is that I wasn’t at all aware of the gulf that separated the material and sensuous world of science, and the textual and disembodied world of history and philosophy of science. It was as if I had lost the ability to experience the material and sensory qualities of the laboratory, as if I saw the world of science through the textual spectacles of history and philosophy of science. To the extent that when, occasionally, I visited laboratories, I only ‘saw’ papers, inscriptions and documents, maybe a few images here and there.

[..]

(thanks to Martha Lourenco at the Museu da Ciencia da Universidade Lisboa for inviting me to give the talk — this post contains the introduction only, the rest needs revision before being put online).

Will this become the abstract of the 2010s?

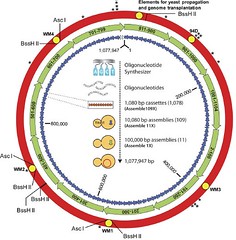

We report the design, synthesis, and assembly of the 1.08-Mbp Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 genome starting from digitized genome sequence information and its transplantation into a Mycoplasma capricolum recipient cell to create new Mycoplasma mycoides cells that are controlled only by the synthetic chromosome. The only DNA in the cells is the designed synthetic DNA sequence, including “watermark” sequences and other designed gene deletions and polymorphisms, and mutations acquired during the building process. The new cells have expected phenotypic properties and are capable of continuous self-replication.

From Gibson et. al., “Creation of a Bacterial Cell Controlled by a Chemically Synthesized Genome” in today’s issue of Science. Et al. in this case of course includes Craig Venter, who has now made an important step towards synthetic life.

It’s not really synthetic life yet— it’s ‘just’ a synthetic genome, which has been designed in the computer, assembled from chemically synthesised oligonucelotides, and then put into a recipient cell, where the new synthetic genome took over control, thereby creating a new Mycoplasma species. Nevertheless — it’s pretty mindblowing.

It’s not really synthetic life yet— it’s ‘just’ a synthetic genome, which has been designed in the computer, assembled from chemically synthesised oligonucelotides, and then put into a recipient cell, where the new synthetic genome took over control, thereby creating a new Mycoplasma species. Nevertheless — it’s pretty mindblowing.

In this video, Venter shortly explains the work behind the paper, and then discusses the many possible applications, including vaccine production. He predicts, for example, that the production of flu vaccine can be speeded up considerably, making it both cheaper, more reliable, and more on-demand.

Tons of ethical, religious, environmental etc. issues will of course be raised in the wake of this.

One of my favourite medical technology websites, Medgadget, is launching a Medical Museum Competition.

They suggest you visit your local medical museum:

Chances are that no matter where you live, there is a medical museum nearby. Maybe it’s an overlooked building in the center of your city, or a hospital library. Inside, you’ll find bizarre specimens, important documents, and yes, medical gadgets.

So, write a report about it, showcase its treasures, explain how it grew out of the contributions of scientists and clinicians in the local area, etc. To this end, Medgadget has implemented a dynamic website where you create an online presentation — upload pictures, file a report, embed videos, etc. to “impress the judges”.

The museum presentation shall be finalised not later than Sunday, June 13. The grand prize is an Apple iPad — and the honour, of course.

More here.

Just got an email saying that the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim has announced a postdoc position to study “the production of images of the interior of the human body on the cellular level”. See more about the background for the project here: The salary is splendid: 438.500 NKK annually. More info from Merete Lie, merete.lie@ntnu.no. Deadline is 20 June, 2010.

Large bladder stone, encased in silver and carried by the patient (1652). Medical Museion, public exhibition.

Oslo-based medical photographer Øystein Horgmo (The Sterile Eye) made an incognito visit to Medical Museion two weekends ago — and has now written a very nice travel report + slide show, which includes some of the best photos of our artefacts on display that we’ve ever seen in the public domain.

I’ve never had a chance to meet Øystein in real life — hope he will be back less incognito soonish!