What’s interesting in the interview with Craig Venter in Der Spiegel last week is not, as most commentators suggest, that Venter stands out as a self-aggrandizing jerk. What’s really interesting is his pessimistic view on the medical implications of genomics and ‘personalised medicine’:

SPIEGEL: So the Human Genome Project has had very little medical benefits so far?

VENTER: Close to zero to put it precisely […] I was just in Stockholm for the 200th anniversary of the Karolinska Institute. The first presentation was about the many achievements the decoding of the genome has brought. Then I spoke and said that this century will be remembered for how little, and not how much, happened in this field.SPIEGEL: Why is it taking so long for the results of genome research to be applied in medicine?

VENTER: Because we have, in truth, learned nothing from the genome other than probabilities. How does a 1 or 3 percent increased risk for something translate into the clinic? It is useless information.SPIEGEL: [What about] the kind of personalized medicine that genetic researchers have always touted? Each person would get his or her own personal treatment that is tailored precisely to that person’s genetic make-up?

VENTER: That was another one of these silly naïve notions that was out there. It’s not, ‘Oh, we know your genome, we’re going to make this drug for you.’ That will never happen.

Reminds me that ‘personalised medicine’ is an excellent topic for a historical exhibition.

I’m thinking of the

I’m thinking of the  I’ve only read about it on their website, so maybe I’ll change my mind if I visit it IRL.

I’ve only read about it on their website, so maybe I’ll change my mind if I visit it IRL.

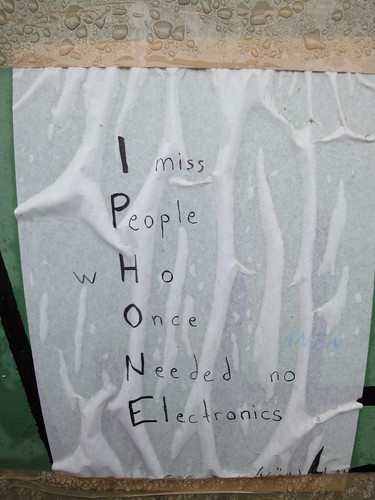

Despite Rosen’s focus on the legal aspects of our eternal exposure on the web, the most interesting aspect of the article is his discussion about the emergence of new social norms regulating our online presence. He has actually “been at dinners recently where someone has requested, in all seriousness, ‘Please don’t tweet this’”.

Despite Rosen’s focus on the legal aspects of our eternal exposure on the web, the most interesting aspect of the article is his discussion about the emergence of new social norms regulating our online presence. He has actually “been at dinners recently where someone has requested, in all seriousness, ‘Please don’t tweet this’”.

In the monograph

In the monograph

For example, we experimented with an aesthetic approach to aging in

For example, we experimented with an aesthetic approach to aging in