Formerly announced workshop ’Communicating Medicine: Objects and Objectives’—held Friday 7 March at the Centre for History of Science, Technology and Medicine (CHSTM) in Manchester—gathered over 40 scholars and curators, mainly from the UK.

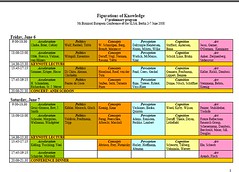

There were nine presentations in all. One each from Science Museum (London), Museum Boerhaave (Leiden), the Wellcome Collection (London), and the Sedgwick Museum (Cambridge), and another five from us here at Medical Museion (Copenhagen): by Søren Bak-Jensen, Susanne Bauer, Jan Eric Olsén, Camilla Mordhorst and myself (see full programme here and here).

Altogether this was a varied and inspiring day about medical museum exhibitions and collections. I’m afraid I was a trifle too involved in the discussions to be able to give a fair resumé of what went on. Suffice it to say I was particularly concerned with Francis Neary’s (Sedgwick Museum) contribution, because Francis brought up the notion of ‘things-that-talk’ in connection with his (otherwise beautifully crafted) argument about machines and instruments as agents.

As readers of this blog may have noticed, Adam and I have recently had some serious doubts about the usefulness of the ‘things-that-talk’ metaphor (see here, here and here), so Francis’s argument gave rise to some critical questions in the discussion that followed. Why impute agency to instruments? What do we gain from doing so?

Also raising lot of discussion was Søren’s paper on collecting biomedicine and the experiences of acquiring contemporary biomedical artefacts during the University of Copenhagen Medical Faculty Garbage Day last June:

Søren’s presentation made me think of former British Museum Director Robert Anderson’s point that ‘acquisitions are the life blood of museums’. Or to put it another way: research can be seen as the soul of museums, and exhibitions their public face and rationale for public funding—but the incessant acquisition of new artefacts provides the life-sustaining nourishment for museum institutions.

I’m not sure that all medical historians or medical museum curators today are fully aware of the consequences of Robert Anderson’s wisdom. So next time we meet we should perhaps discuss how to collect medical objects rather than how to use them for communicating medicine?

(John Pickstone listening attentively)

(John Pickstone listening attentively)

Altogether a most enjoyable day, well worth the trip and air traffic delays, and very well organised by CHSTM’s outreach officer, Emm Barnes:

Btw. did anyone else take better notes than I did?

(

( (

(