Universities aren’t precisely drawback-free zones — yet I’ve been thinking about how privileged university-based blogs are when I see some of our science blogging peers who (have to, or feel they have to?) fill their blogs with banner ads and Google Adsense links. A university financed blog doesn’t have to think about blog ad networks, average payment per blog post, pay-per-clicks, pay-for-post marketing strategies, banner advertising spending, or speculate about how to provide better value for advertisers. And we don’t have to meet with target audience advertising agencies and their ilk. That’s a privilege.

Yes, if we shall believe the Aarhus Network for Science, Technology and Medicine Studies which is hosting a one-day conference in Aarhus, Denmark, 23 October, under the heading ‘Challenging hyperprofessionalism: The intradisciplinarity of science, technology and medicine studies’.

Yes, if we shall believe the Aarhus Network for Science, Technology and Medicine Studies which is hosting a one-day conference in Aarhus, Denmark, 23 October, under the heading ‘Challenging hyperprofessionalism: The intradisciplinarity of science, technology and medicine studies’.

To present “the richness of what is going on across the disciplines”, the organisers invite “research based papers or posters, including work-in-progress, broadly within science, technology and medicine studies”, especially contributions that address the intradisciplinarity issue.

Each paper will only be allotted 20 minutes for presentation and questions (not much time, really!). Titles and 100 word abstracts are due 8 October (send to idenklk@hum.au.dk). Slightly more info here.

Following two succesful earlier meetings (in Stockholm in 2006 and in Gothenburg 2007), the Swedish medical history network organizes its third conference, again in Stockholm, on Thursday 29 January 2009. The main item on the meeting agenda is the planned project for writing the history of the Karolinska Institute, founded in 1810, and today one of the world’s leading medical research universities. As the project involves up to ten Swedish medical historians in 2008 and 2009, it will probably dominate the meeting, but the organizers promise that there will be plenty of time for presentation of other current research projects as well. Conference language is Swedish, but you don’t need a Swedish passport to attend. For inquiries, contact Roger Qvarsell, roger.qvarsell@isak.liu.se, http://www.isak.liu.se/temaq/rq/presentation.

Last year, this blog participated in an online survey of medical blogs undertaken by Ivor Kovic, Ileana Lulic and Gordana Brumini at Rijeka University School of Medicine in Croatia. Now they have published the results in a paper titled “Examining the medical blogosphere: an online survey of medical bloggers” in the last issue of Journal of Medical Internet Research, one of the top-ranked journals in the health informatics.

Among the results:

- 6 out of 10 medical bloggers are men (more balanced than I thought)

- 1 out of 3 is a physician (that’s pretty much — will probably grow)

- over 50% have published a scientific paper (impressive!)

- 1 out of 4 medical bloggers prefer to be anonymous (bad habit!)

- 60% of the respondents spend 20 hours or more per week on the internet (not unsurprisingly)

In other words, the typical medical blogger is a male medical doctor with some scientific training who spends most of his spare-time on the internet. Not surprising, I guess 🙂

You can also see a summary of the report in this slide show presentation.

A group of people from geography and STS departments at University College London, Cambridge and Southampton (Gail Davies, Kezia Barker, Brian Balmer, Richard Milne, and Rob Doubleday) have put together an online reader on the geographies of contemporary technoscience.

“Part of a more general ‘spatial turn’” (i.e., yet another turn!), the explicit aim of the project is to draw attention to the way that space matters in the production of science and technology and to the implications of the circulation of expertise and materials in the situating of science and technology.

“Part of a more general ‘spatial turn’” (i.e., yet another turn!), the explicit aim of the project is to draw attention to the way that space matters in the production of science and technology and to the implications of the circulation of expertise and materials in the situating of science and technology.

A nifty web resource of potential great use also for people interested in medical science studies and the contemporary history of medicine. See the introduction to the project here.

The 10th Lennart Nilsson Award for scientific photography has been given to Anders Persson, Director of the Center for Medical Image Science and Visualization (CMIV) at Linköping University in Sweden, for his techniques for capturing 3D images inside the human body. Persson and his colleagues at the CMIV produce the images by combining ultrasound, MRI- and PET-scanning images.

The 10th Lennart Nilsson Award for scientific photography has been given to Anders Persson, Director of the Center for Medical Image Science and Visualization (CMIV) at Linköping University in Sweden, for his techniques for capturing 3D images inside the human body. Persson and his colleagues at the CMIV produce the images by combining ultrasound, MRI- and PET-scanning images.

The technique, which is particularly useful for post-mortem imaging, has been featured on CBS’s Crime Scene Investigaton show. Says the award foundation in their press release:

Persson’s imaging methods combine cutting-edge technology with great artistry and educational value. He reveals the hidden mysteries of the body with unique precision, producing images that can be understood and interpreted by the lay public and experts alike.

To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Lennart Nilsson Award, a photo exhibition will be arranged at Galleri Kontrast in Stockholm, 11 October – 2 November. Further info from Staffan Larsson, Lennart Nilsson Award Foundation, staffan.larsson@ki.se

We use to think of hospitals and clinics as almost history-free zones. But sometimes medical historical images, artefacts and records show up in the most unexpected medical spaces.

Like last week, when I spent a couple of days with our daughter in the neonatal clinic at the Danish National Hospital, i.e., where they care for babies that are born too early (down to 24th gestation week!) and other newborns with more or less serious medical conditions (fortunately ours was a less serious case).

The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators, CPAPs, automatic infusion pumps. Beep-beep everywhere. Definitely a mobile free zone, and much more so than in an aircraft: the staff probably meant it seriously when they said that a single phone on standby can stop all the infusion pumps in the ward!

The neonatal clinic is a really fascinating place for an historian of contemporary medicine and museum curator. It’s packed with monitoring systems that measure the basic vital parameters. They use all kinds of high-tech electronic gadgets: incubators, CPAPs, automatic infusion pumps. Beep-beep everywhere. Definitely a mobile free zone, and much more so than in an aircraft: the staff probably meant it seriously when they said that a single phone on standby can stop all the infusion pumps in the ward!

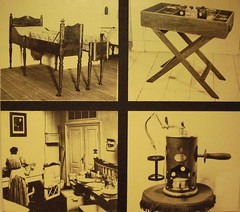

But they had more on show than science fiction-looking technology for our future collections. Behind the toilets, in a short hallway leading to the parents’ day area, I discovered four large images of museum artefacts — in fact, images of 19th century objects on display in the 1970s permanent exhibition of the former Medical History Museum (now Medical Museion):

The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements.

The bed and the Lister carbolic spray are still on display in our permanent galleries, although nowaday in other arrangements.

None of the items on the pics have much to do with neonatal care and the print quality is not exactly good. Yet some time, someone (maybe the head of the clinic?) decided to hang them there, partly stuck away. Why? To add a slight historical touch to the high-tech ambience of the clinic? To create some balance?

These images made me think of the geography of the medical historical heritage. The medical heritage is not just a heap of things in medical museums — it is a dynamic field, which is distributed and put to use in a variety of spaces over time. Medical historical images, artefacts and records circulate between patients, medical staff, manufacturers, clinics, hospital storage rooms, archives, collections, and exhibitions (and are sometimes pulled out of circulation and deposited as heritage sediments in closed museum repositories).

Heritage is a very different thing when it appears in designated museums like ours (a sort of ‘temple’ for medical heritage) and when it is distributed, even in the form of images, around the clinics of the Danish National Hospital and in other hospitals, institutions, organisations and private homes in the region, where it functions more like memorial shrines.

The spatial distribution and dynamic relation between the ‘worship’ of heritage in temples and shrines is an interesting topic. The way medical museums collect, manage, display and make sense of this heritage is very much dependent on how the overall geography — including the production, circulation, distribution, consumption, performance and eventual destruction — of local heritages is understood and conceptualised.

Anybody willing to expand on this? Anyone out there who can develop his/her thoughts on the ‘geography of the medical heritage’?

In yesterday’s issue of Public Library of Science: Biology (vol. 6, Sept., e240 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060240) bioscientists Shelley Batts, Nicholas Anthis, and Tara Smith have an interesting article titled “Advancing Science through Conversations: Bridging the Gap between Blogs and the Academy”.

The authors notice that scientific institutions have been pretty slow to adopt the blog medium, in spite of the fact that both institutions and bloggers have a common interest in advancing public engagement with science. They suggest that:

By combining the credibility of institutions — trusted gate-keepers for scientific truth — with the immediacy and networking infrastructure of blogs, we believe that these shared goals can be better served with benefits to both partners.

More specifically, they propose “a roadmap” for turning blogs into educational tools for institutions (mainly universities). They present examples of collaborations that can serve as a models for others to emulate, and they offer suggestions for improving upon blog platforms to make them more acceptable to institutional hosts.

In many respects, this is all very commendable. The PloS-article describes and evaluates a number of interesting institutional blog initiatives, like Rudd Sound Bites (www.ruddsoundbites.typepad.com), the ChemTools blog (chemtools.chem.soton.ac.uk/projects/blog, the Berkeley Lab Energy and Environmental Research Blog (bleer.lbl.gov), and the Oxford Internet Institute (www.oii.ox.ac.uk), and so forth. Very useful stuff, which many academics (and not only scientists) could learn a lot from.

One important critical point though. The authors seem oblivious of a crucial aspect of the relationship between individual science bloggers and institutions engaged in science communicating, namely the power dynamics involved. True, they are aware of the fact that the science blogosphere is a bottom-up driven network. But they don’t expand this observation into an analysis of the conflict patterns involved.

For a thorough understanding of how blogs and institutions relate to each other in a science communication network, however, one has to take such potential and actual conflict patterns into account. After all, institutional actors have quite different set of political and economic agendas than singular science actors.

This was in fact one of the themes we discussed in the ‘The Public Engagement of Science and Web 2.0′ session at the 10th Public Communication of Science and Technology conference in June (see paper here).

Generally speaking, I’m afraid the growing literature on science blogging reflects a widespread naïve view of the medium. Like the authors of the PLoS-article, most commentators on blogging as a genre of science communication are pushing for the medium with their critical mindset on standby, even disabled. In other words, there is too much technological optimism, and too little critical analysis involved in the current discourse on science blogging.

As several historians of the contemporary life sciences have pointed out, much of biological thinking is metaphorical. Not least in genomics. The race for the human genome in the 1990s and much of subsequent postgenomics has been guided by a series of metaphors that draw on linguistics, management science, and information and communication science.

Accordingly, computer science analogues have flourished. The genome is said to contain the ‘code’ or ‘blueprint’ for development, the ribosomes ‘read’ the instructions, and ‘information’ is carried on to proteins through ‘transcription’ and ‘translation’ (see, for example, Susanne Knudsen’s analysis of the ‘code’ metaphor in ‘Communicating novel and conventional scientific metaphors: a study of the development of the metaphor of genetic code’ (Publ. Commun. Sci., vol 14, pp. 373-92, 2005).

But linguistic and computer analogies are not very helpful when it comes to the proteome with its estimated half million or so specific protein-protein interactions (the ‘interactome‘). What kinds of metaphors are available if one wants to capture this rich and complex protein universe?

But linguistic and computer analogies are not very helpful when it comes to the proteome with its estimated half million or so specific protein-protein interactions (the ‘interactome‘). What kinds of metaphors are available if one wants to capture this rich and complex protein universe?

This is not just an academic question, but also a practical one: metaphors are indispensible tools for science communicators. So reflective answers to this question would be very useful for science and medicine museums that wish to present protein science and proteomics in their displays — as we are planning to do in a small extramural exhibition next year.

Browsing the literature gives a few tentative hints. Proteins are usually spoken about in quite mundane metaphorical terms, a far cry from the informational control center terminology that guided the rise of genomics. Thus the only major historical overview in book form so far, written by now retired protein researchers Charles Tanford and Jacqueline Reynolds (Oxford UP, 2001), is aptly titled Nature’s Robots.

Others — for example this University of Washington site — liken proteins to the ‘work-horses’ of the life processes. The two images reproduced in this post also suggest metaphors that gesture towards a mechanical, workman-filled world. The small image above illustrates a proposed ‘cogwheel model’ for signal transduction across membranes, involving a transmembrane protein receptor in the form of a four-helical coil. The model was on the cover of Cell (8 September, 2006), explained as “a gear box with four cogwheels” (credit: Martin Voetsch, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology).

The second image is also a ‘cogwheel model’, in this case of a protein complex in yeast cytoplasm that contributes to mRNA decay (credit: European Molecular Biology Laboratory; from The Scientist 22, issue 9, p. 55, 2008)

The second image is also a ‘cogwheel model’, in this case of a protein complex in yeast cytoplasm that contributes to mRNA decay (credit: European Molecular Biology Laboratory; from The Scientist 22, issue 9, p. 55, 2008)

There are other interesting metaphors around. University of Texas oncologist Gus Pappas has likened the proteome to ‘a play’s cast’, a list of the ‘Dramatis Personae’ of the cell (see ‘A new literary metaphor for the genome or proteome’, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, vol. 33 (1), p. 15, 2006).

Maybe one could try further along these lines. Not in terms of literary or theatrical metaphors though, but in terms of politics. For example, imagine the cell as a city like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, where a small elite caste of nucleic acids stand against a diverse multitude of life-producing worker-proteins — a proteomic metaphor that reflects some of the basic aspects of capitalism.

Although I’ve spent the better part of the last two decades writing biographies and reflecting on biography as a genre, I’ve always been very fond of auto-biographies, especially those of academics and professionals.

The reason for this fondness is probably that autobiographies stimulate my fantasies about how my life trajectory could have been different. By engaging in an inner dialogue between the autobiographer’s and my own voices, it’s not only possible to come a little closer to the other’s mind and practice, but maybe one can even learn a little more about one’s own decisions, many mistakes and occasional successes.

It doesn’t really matter if the story is accurate or not. After all, autobiography is closer to fictional writing than biography, which in turn is closer to faction (history). For that reason autobiography is a better genre than biography for the kind of ‘souci de soi’ (care of self)-practices, which Pierre Hadot, and later Michel Foucault, have explored (in Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault and The History of Sexuality, respectively).

I use to read all kinds of academic and professional self-writing with great pleasure. But for job-related reasons I keep a special eye on medical memoirs and autobiographies.

Frankly, more often than not, this feels more like a duty than a pleasure. Because medical self-writing is largely dominated by physicians and medical researchers who sometimes seem to believe that their lives are important just because they happened to construct a useful apparatus, or described a rare syndrome, or made an important physiological discovery.

True, such elite narratives can be potent sources for later medical history writing. But they are not necessarily recipes for interesting memoirs or autobiographies. The historical importance of a life’s work is often reversely proportional to the richness of the life lived. Moreover, the literary quality of many of these medical doctors’ autobioi varies enormously, most of them gathering around the lower end of my aesthetic sensibility meter. Most are quite tedious, few stick to my memory.

However, the lives of people from other medical professions — nurses, midwifes, public health workers, medical technicians and so forth, that is, people who have not been Very Important People but who sometimes just happen to have lived enigmatic and engaging lives — not seldomly make for more interesting reads.

Unfortunately, these other medical professionals rarely get the brilliant idea to go about writing their autobiography. Not Very Important People in the medical professions apparently do not believe they have something interesting to tell. So each time I come across one of these medical staff autobioi I get pretty excited.

As for example the other day, when my Google Reader announced a blogpost by Norwegian medical videographer Øystein Horgmo titled ‘How did it come to this?’. It is touching because he focuses on how his girlfriend’s little sister died of leukemia a few years ago and how this experience propelled him to into combining his former, pretty disparate, professional trainings in nursing and video filming to become a medical videographer (and in my opinion a very reflexive one).

Horgmo’s essay is pretty short and not stylistically sophisticated. But it is nevertheless a fine example of how autobiographical writing by medical professionals can fulfil the function of ‘care of self’. As Horgmo himself writes towards the end: ‘That’s my story. I’ve found the sense of meaning I was searching for’.