Camilla’s post about Robert Wilson’s recent lecture at Stanford reminded me of David Pantalony’s essay in the July issue of the History of Science Society Newsletter:

Why does a control panel for a computer from 1950 attract several viewers in the architecture and design galleries of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, while similar objects rest unnoticed in storage rooms and science museums around the world?

Referring to Joshua Taylor’s Learning to Look (1981), David reminds us that we too often stop considering objects as soon as we have recognized them. Putting them in other surroundings (like the control panel in MOMA), however, makes it easier to reconsider them. Thus, the main challenge with recent technological artifacts, David points out, “is to prod researchers, the public, and students to move beyond recognition, and to stimulate alternative perspectives and inquiry”.

One way of doing this is to teach history classes about material history. David shares his experiences from teaching an artifact-based historical seminar for University of Otttawa students at the Canada Science and Technology Museum (where he works as a curator in physical sciences and medicine). He begins the artifact sessions´— which take place in the aisles of the storage facilities — by asking the students to examine the basic properties of the artifacts: “materials, colors, finish, markings, modifications and manufacturing labels”, followed by questions about their history, design, and function. Then follows more analytical questions about the identity of objects and their aesthetic qualities, etc:

The key to this exercise is a careful and wide-ranging interrogation of artifacts. The more the students examine, the more questions appear. With persistent questions, they begin to transcend the traditional narratives determined by the artifact’s name and classification. They start thinking critically about specific features and how these features represent choices and context of makers and users. Where there is choice there is culture, context, and history. Why these kinds of markings? Why this construction? Why this style of container? Why this kind of component over another? Why this kind of material?

The cultural analysis of artifacts requires students to ask about “hidden beliefs, values, associations, and meaning”. They also learn to examine artifacts from a different culture, for example, contrasting Western post-war medical technology with healing artifacts from aboriginal cultures.

Not only are David’s experiences useful for curators in sci-tech-med museums — they are also an inspiration for those of us who try to integrate university teaching with museum work. Read the whole essay here.

PS: David sends a nod to the discussions on this blog about the use of MRI scanners in exhibitions; see Søren’s post here and Hans’ post here.

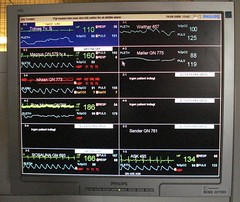

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’.

The vital data from each patient are displayed on a monitor above the bed (incubator in the serious cases). All twelwe patients in the ward are then summarized on a big screen in the ‘control room’. If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient.

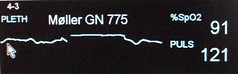

If, for example, the oxygen saturation level falls below 85%, an alarm sounds, a yellow pop-up screen flashes on screens in the ‘control room’, and a nurse or physician goes to attend to the little patient. On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.

On the monitors a new biomedical identity was emerging: curves and numbers representing the two variables that the doctors had chosen to measure: oxygen saturation level and pulse rate.