The theme of the 6th annual conference in the ‘Science and the Public’ series, to be held at Kingston University, London, on 2-3 July 2011, is ‘A Quarter Century of PUS: Retrospect and Prospect.’

The theme of the 6th annual conference in the ‘Science and the Public’ series, to be held at Kingston University, London, on 2-3 July 2011, is ‘A Quarter Century of PUS: Retrospect and Prospect.’

The meeting takes the publication of the Royal Society’s report into the public understanding of science (the Bodmer Report) in 1985 as its point of departure. Introducing what Brian Wynne and others later called ‘the deficit model’, the Bodmer Report stimulated a widespread interest in the public understanding of science (PUS) in the UK and later in the rest of Europe.

The aim of the meeting is to take stock of where public understanding of science stands now, 25 years later:

Is there still (or was there ever?) a ‘public understanding of science movement’ and if so where is it and what form does it take? Is it now defined by ‘engagement’, by ‘dialogue’ or by some other mode of public interface? Is the deficit model dead and if so has it been properly buried or does it still haunt our corridors? What else is there? What shape does the PUS field now have? Is there a comparable agenda of concerns to that defined by Bodmer and if so what is it? And in what direction(s) should work now be going? What about the critical responses? Where have they taken us and where might they be taking us in future? Is there a consensus or do we remain a field in conflict with entrenched opponents, if no longer actively at ‘war’, then hunkered down in separate bunkers refusing – or simply neglecting – to speak to each other? Is there, indeed, a language we share to communicate with each other, let alone the public?

The organisers invite papers and panels that address themes and issues like:

- reflections on the Bodmer Report and its historical, sociological and/or cultural significance;

- the PUS movement and its off-spring;

- how engaged is ‘engagement’ and how dialogical is ‘dialogue’?

- the prospects and circumspects of ‘citizen science’;

- the new science communication – education, entertainment … or irritation?

- new forms and modes of popularisation;

- technoscience and its consumption;

- science, art and culture – changes, developments, continuities;

- theorising PUS

- methods of research – new developments, new thoughts, new proposals;

- new agendas for the science/public relationship and its academic study.

<250 words abstracts to l.allibone@kingston.ac.uk or s.locke@kingston.ac.uk not later than 28 February 2011.

More info here.

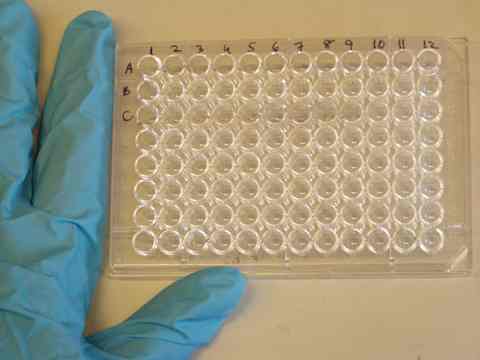

One of my favourite objects for acquisition and display from the world of biomedical and clinical laboratories is the microplate (microtiter plate, microwell plate).

One of my favourite objects for acquisition and display from the world of biomedical and clinical laboratories is the microplate (microtiter plate, microwell plate). What about the history of the microplate? Professional historians of medicine and/or technology haven’t paid much attention to the unassuming plastic lab device. After a few minutes on the web, however, I found out that the earliest microplate seems to have been constructed by the Hungarian medical microbiologist Gyula Takácsy (1914-1980). The Hungarian National Center for Epidemiology writes on

What about the history of the microplate? Professional historians of medicine and/or technology haven’t paid much attention to the unassuming plastic lab device. After a few minutes on the web, however, I found out that the earliest microplate seems to have been constructed by the Hungarian medical microbiologist Gyula Takácsy (1914-1980). The Hungarian National Center for Epidemiology writes on