Glem ikke at tænde for DR2 Deadline i aften. Vores egen psykiatrihistoriske specialist Jesper skal tale med Adam Holm.

“Schenken heisst Anderen etwas von dir zu geben” (to give means to give something of yourself to others):

Biomedicine on Display wishes all our readers a merry xmas and a very happy new year.

(thanks to Roger Cooter, UCL, for the xmas card we’ve borrowed this image from)

“Schenken heisst Anderen etwas von dir zu geben”. Museionblog ønsker alle sine læsere en God Jul og et rigtigt Godt Nyt År.

(tak til Roger Cooter, UCL, for julekortet vi har stjålet billedet fra)

Well done, but the fingers are creepy.

[biomed]NhnYipRAp3M&feature=player_embedded[/biomed]Thanks to Street Anatomy.

One of my favourite fellow bloggers, medical photographer Øystein Horgmo, has just written about how he was recently invited to document a family taking farewell of a young father in an intensive care unit.

One of my favourite fellow bloggers, medical photographer Øystein Horgmo, has just written about how he was recently invited to document a family taking farewell of a young father in an intensive care unit.

It’s a moving story. But what actually caught my interest was this painting (by medical doctor Joseph Dwaihy and artist Sara Dykstra), which Øystein uses the illustrate the story.

Based on a photograph from the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center’s first intensive care unit, circa 1955 (read more here), the painting is reminiscient of Norman Rockwell-realism. Like Rockwell, Dwaihy and Dykstra portray people in mundane situations. It’s people who play the primary role. The instruments are background props.

Compare Dwaihy and Dykstra’s painting of the 1955 ICU motif with a photo of a contemporary ICU unit. Today, there are indeed still people (a patient, a doctor, maybe a relative) around—but they seem to play a secondary role to the instruments.

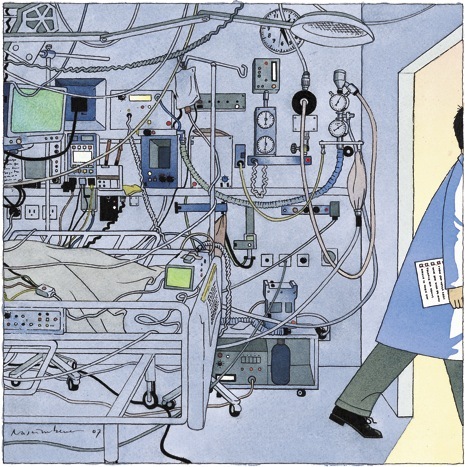

In the cartoon below, the central role of instruments in an ICU is emphasized. The patient is invisible, the doctor is on his way out. Here the ICU is all about the instruments:

As a newcomer to a social networking service called Facebook (maybe, you’ve heard about it?), I’m intrigued by the fact that so many profile face images show only parts of the face. In this random selection of profile images displayed when I click “People You May Know“, 50% show part-faces only:

It seems to be a fairly new fashion (maybe a couple of years old). Does it mean “I’m not so naïve that I believe one can present anything but a partial personality on Facebook”? Partial faces, partial friends. Or is it a general trend in photography these days?

I cannot resist this wonderful comment on the writing style of Giorgio ‘bare-life’ Agamben (or rather the crowd of Agambians):

1. Take a suitably lengthy, informative, and arcane wikipedia entry – my suggestion is this on Noah’s Ark.

2. Use as many of the original language reference and most arcane features in said entry to trace a genealogy of said “symbol” (remember to introduce the most esoteric or unusual by beginning with “As everyone knows”), i.e “As everyone knows Muhammad ibn al-Tabari’s 915 work تاريخ الرسل والملوك suggests the donkey was the last animal on the ark, and the means by which Satan entered”.

3. Make analogy between said entry and a feature of the current geo-political situation (i.e. Noah’s ark as symbol of vanguard exodus), i.e. “the donkey, as the entrance of the Satanic principle into exodus, is the prophetic sign of its fatal contamination in modernity by the biopolitical reduction of the subject to bare life.”

4. Remember to make every such sign or symbol reversible: so “the donkey is at the same time the messianic sign of bare life transfigured: And Jesus, when he had found a young ass, sat thereon; as it is written” (John 12:14).

5. Add in some contemporary reference, perferably to pornography / contemporary media events / some index of the present (ok, so the donkey conceit will now end…)

6. And loop around again.

Hilarious, but sadly realistic. I’ve lived long enough to see a row of academic fads—Marx, Bourdieu, Foucault, Latour, etc.—glow like supernovae and make their impact on term papers and dissertations, and then slowly begin to fade away. When will students ever learn?

(quoted from No Useless Leniency; thanks to Paolo for the tip)

The increased digitalisation of science and technology is problematic for museums as institutions for the preservation of the material cultural heritage.

The increased digitalisation of science and technology is problematic for museums as institutions for the preservation of the material cultural heritage.

The reasons is that we usually think of digital information as something ‘immaterial’, a mere collection of zeros and ones that —as Jean-François Blanchette (Dept. of Information Studies, UCLA) points out—are considered “wholly independent from the particular media on which it resides (hard drive, network wires, optical disk, etc.) and the particular signal carrier which encode bits (magnetic polarities, voltages, or pulses of light)”.

But, suggests Blanchette, “however immaterial it might appear, information cannot exist outside of given instantiations in material forms”. Building on, among others, Philiip Agre’s Computation and human experience (1997), Blanchette discusses the material foundation of digital information:

It suggests that various factors, including the trope of immateriality, have obscured the physical constraints that obtain on the storage, circulation, and processing of digital information, resulting in inadequate theorization of this fundamental dimension of information systems. In fact, computing systems are suffused through and through with the constraints of materiality, and the computing professions devote much of their activity to the management of these constraints, as manifested in infrastructure software.

In Blanchette’s analysis computing is material through and through:

But this materiality is diffuse, parceled out and distributed throughout the entire computing ecosystem. It is always in subtle flux, structured by the persistence of modular decomposition, yet pressured to evolve as new materials emerge, requiring new trade-offs. This project thus argues that, in a very literal and fundamental sense, materiality is a key entry point for reading infrastructural change, for identifying opportunities for innovation that leverage such change, and for acquiring a deep understanding of the possibilities and constraints of computing. This understanding is not particularly provided by exposure to programming languages. Rather, it requires familiarity with the conflicts and compromises of standardization, with the principles of modularity and layering, and with a material history of computing that largely remains to be written.

In other words, this is food for thought for those of us who are interested in the materiality of contemporary computational biomedicine. Read the whole paper (submitted to the Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology) here.

(thanks to Haidy L. Geismar for the tip)

Diskussionen om hvilke farve vi skal have på vægge, paneler og dørkarmer i tre rum på 1. sal i Akademibygningen er gået igang. Meningerne i huset er delt, og udefra begynder gamle og nye venner at blande sig. Skal vi male de tre rum i efter den farvearkæologiske rapports vurdering af de oprindelige farver (ultramarine vægge med mørk gammelrosa paneler) eller skal vi vælge nogle neutrale grå eller lyse pastelnuancer? Her er nogle uddrag af diskussionen på Bente’s Facebookvæg:

- BVP: Dagen er gået op i farver.. ikke så festligt som det lyder. Skal vi male tre rum i akademibygningen efter konservatorrapportens tilnærmede vurdering af, hvad der oprindeligt var smurt på væggene (ultramarine vægge med mørk gammelrosa paneler) eller vælge neutrale grå nuancer?..

- CSHJ: Er helt klart mest til gråt…

- TLJ: ultramarine vægge med mørk gammelrosa paneler KLART!

- WI: Jeg siger, rød og hvid

- NR: Jeg stemmer klart for ultramarin. Kan man hedde Museion, kan man osse have blå vægge. Det matcher jo så fint jeres gæsters ansigtskulør 🙂

- ThS: Ja, det var en dag i vildrede. Først snakkede vi med repræsentanter fra KUAS, det arkitektfirma som står for opgaven og så den dygtige malermester som har ultramarineblå på hjernen. Så inviterede vi fire af vores unge garde (AB, AS og LL) til en diskussion nede i farveprøverummene (det var da stemningen begyndte at tippe til fordel for dybblå+mørkerosa), og til sidst kom BB fra Kunstindustrumuseet forbi og stillede nogle gode skarpe spørgsmål.

- AP: Hold da op det lyder som vi får et Meget farve rigt udstillingsrum 🙂

- AB: Ja, blå vægge, brune paneler og hvide vinduer/loft giver et optimalt udstillingsrum.

- BVP: Bør måske tilføje at “mørk gammelrosa” mere ligner, hvad AB kalder “sommerhusbrun”. Hører gerne flere kommentarer, for klogere blev jeg ikke.

@CSHJ: hvorfor? Æstetisk eller funktionelt.. vi har selv været der halvdelen af dagen, men …er bange for, det bliver for intetsigende..

@TLJ og NR: interessant, at to frafaldne museionianere kan svare så klart ultramarint.

@WI: Fodboldtosse..

@ThS: Et skridt frem, to tilbage..

@AP: og i hvert fald ikke kedeligt..

@AB: det er rart at høre dig sige det… jeg ved jo, du mener det inderst inde.. - ThS: Jeg nåede ikke at få fat i arkitekten inden jeg gik hjem i dag (sulle nå at hente J. i vuggis), men vil prøve at ringe fra toget i morgen.

- TLJ: BVP, nu har jeg malet en del små figure i min “ahem” barndom, så ultramarine står lysende klart for mig. Samtidigt ville det være fantastisk med farver! selv af den brun rosa slags. Huset er en genstand i sig selv og bliver aldrig et “white cube” udstillingslokale. Så måske ville farvevalget fremhæve huset. Den grå nuance er tit den lette vej til at neutralisere rummet i forhold til udstillingen og det ligenetop i museions tilfælde lidt kedeligt.

- BVP @ WI: et hus i fodboldfarver og alle fodboldfans vil blive museion-elskere? @ ThS – det er meget interessant – og jeg er enig med dig langt hen ad vejen.. Som jeg ser det, er det et valg mellem på den ene side at få nogle udstillingru…m, hvor selve udstillingen er styrende, ikke de på forhånd valgte farver eller på den anden side sætte farverne efter et tilstræbt “oprindelighedsprincip”, der nok kan diskuteres. Jeg har ikke noget imod farver – og de må gerne være dristige. Men jeg er også nervøs for, at farvevalget her kommer til at løbe af med os. At vi simpelthen ikke ved, hvad det er vi laver.. og så er dristigt måske nærmere dumdristigt.

- WI: Ikke alle af dem, og der vil nogle gange savne et maleri, men alt til kultur tættere på folk sætter, right?

- ThS: Ifølge arkiteten gælder forslaget ikke kun panelerne, men også dørrene, dørkarmene og vindueskarmene ! Det bliver helt vildt — forestil jer 6000 Illumina gene chips mod ultramarin og gammelrose baggrund!

- NR: En konservator kunne komme med den kommentar at Ultramarinblåt ofte blev brugt som underlægningsfarve og dækket af transparente lag, for at opnå en smuk dybde i farven. Jeres vægge har muligvis, og skuffende nok, måske altid fremstået i den ubestemmelige blå-grå tone?

- BVP: DET er en spændende teori NR!! Tak for det bidrag.. ThS, hører du hvad NR siger…

- ThS: Intressant! @ NR: kan du komme med en litteraturhenvisning som styrker dette?!

- NR: wikileaks 😉 Ikke umiddelbart, det va mest ment for et spørgsmålstegn. Har i et bud på datering?

- ThS: Den ultramarina er fra husets start (1787) umiddelbart ovenpå grundningsfarven.

- NR: Jeg ville nok selv kontakte Konservatorskolens monumental afdeling om vejledning. Har i lavet farveundersøgelser andre steder? Måske er det bare nichen, og blev brugt til at tone dagslyset? Først fra 1820érne begyndte man at lave syntetisk …ultramarin, så hvis jeres er lapis lasuli, kunne i måske argumentere for at det ville være en utilgivelig forfalskning at anvende andet end den ægte vare, der er meget kostbar, og ad den vej åbne en mulighed for at satse på det næste lags Limpopoflodsfarvede anvendelighed? Glæder mig meget til at se det endelige resultat!

- BVP: Tak for alle bidrag. Diskussionen fortsætter på http://www.museionblog.dk/hvilke-farver-skal-der-v%c3%a6re-pa-v%c3%a6ggene-og-panelerne-i-vores-tre-nyrestaurerede-udstillingsrum

Und so weiter …

Why do we visit anatomical museums: for curiosity or for learning? (or maybe for some other reason?)

Next Friday, 17 December, Elena Corradini at the Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia organises a seminar on “Visiting an Anatomical Museum: curiosity or training?”:

Anatomical University Museums are the keepers of collections which often are very old and different for their consistence and typology. These museums have a fundamental role for the preservation and valorization of cultural historical‐scientific heritage, therefore must become a place of interdisciplinary synthesis. They represent the progress of studies in the past and for the future, and play their fundamental role for the research and for the promotion of educational activities. This role will allow them to be a service for University students and professors, and to spread scientific knowledge to different audiences. Developing the capacity of museums to work in a network is necessary for them to become centres for the production of knowledge, activities and services.

Speakers include a number of directors and curators from Italian university anatomical museums together with the directors of the Josephinum of Vienna and the Museum of Medical University of Danzig:

- Giovanni Mazzotti, University of Bologna: Visiting an Anatomical Museum: curiosity or training?

- Sonia Horn, University of Wien: The growth of collections for the permanence of an historical Anatomical Museum. The case of the Josephinum in Vienna.

- Roberto Toni, University of Parma: The Anatomical Museum as a research source in the field of

biomedical robotics: the Tenchini project at the University of Parma - Alessandro Ruggeri, Nicolò Nicoli Aldini, Stefano Durante, Vittorio Delfino Pesce, University of Bologna: The visit of the Anatomical Waxes Museum “Luigi Cattaneo” center of in-depth research of the Bolognese medical tradition of XIXth century and of training for modern education

- Ugo Pastorino, National Tumour Institute, Milan: The project for a virtual archive of human body images

- Carla Garbarino, University of Pavia: The anatomical collections of the Museum for the history of the University

- Marek Bukowski, University of Gdansk: An Anatomical collection and Museum of Medical University

- Berenice Cavarra, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia: Medicine and the study of the living being in XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries

- Vincenzo Esposito, Second University of Neaples: Anatomical Museums between past historical identity and present cultural crossbreeding

- Marina Cimino, University of Padua: The birth in a museum or the birth of a museum: the obstetric collection in Padua

- Elena Corradini, Elisa Orlando, Daniela Nasi, Silvia Rossi, Sara Uboldi, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia: POMUI ‐ The Portal of Italian University Museums

- Giorgio Bonsanti, University of Florence; Elena Corradini, Berenice Cavarra, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia; Paolo Nadalini, INP, Institut National du Patrimoine, Paris; Luigi Vigna, Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence; Isabelle Pradier, INP, Institut National du Patrimoine, Paris: A project for the restoration of anatomical waxes

Info from Silvia Rossi or Sara Uboldi, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia (silvia.rossi@unimore.it; sarauboldi@yahoo.it), +39 059 205 5012

(thanks to Sébastien Soubiran for the tip)