Around 1950, ~3 years old.

I have not yet made up my mind as to whether I shall 1) restrict myself to the process of writing about my own life, interspersed with observations about memoir writing (using myself as the empirical case), or 2) also write a full memoir.

The first choice has been my priority so far. I’ve immersed myself in the archive and the process of memoir writing. And I have taken every opportunity to interrupt my readings and note-taking with reflections on what is going on in my mind in the process.

The alternative — writing a full memoir or autobiography —also has its attraction, however, and it feels like a kind of mental abortion to reject this option out of hand.

What has so far dissuaded me from thinking seriously in terms of a full memoir, I think, is the spectre of going public, of having to share private and intimate details about my life. There are too many things in life I still feel ashamed of.

But I am beginning to realise that I don’t really need to go public even if I should decide to write a full memoir text. Because I can also choose to write for the desk drawer (or rather the harddisk).

But I am beginning to realise that I don’t really need to go public even if I should decide to write a full memoir text. Because I can also choose to write for the desk drawer (or rather the harddisk).

Is this really a realistic option for a person like me, who have lived my whole life in writing for the public domain?

The American writer and scholar William Zinsser (best known for his bestseller On Writing Well, 1976; free pdf here) have some interesting thoughts about this.

In a 2006 essay in The American Scholar, Zinsser pointed out that there are many good reasons for writing memoirs “that have nothing to do with being published”:

In a 2006 essay in The American Scholar, Zinsser pointed out that there are many good reasons for writing memoirs “that have nothing to do with being published”:

“Writing is a powerful search mechanism, and one of its satisfactions is that it allows you to come to terms with your life narrative. It also allows you to work through some of life’s hardest knocks—loss, grief, illness, addiction, disappointment, failure—and to find understanding and solace.”

And added that memoir writing can be “an act of healing”.

Zinsser’s point is that you can actually get full personal satisfaction from writing for the desk drawer. It’s of course okay to write for the public, but there are so many positive side-effects of writing privately, that one does not even have to contemplate the public alternative.

Still, the idea of writing only for private use is pretty anathematic for an intellectual like me, who have spent my whole life writing for publication. Private writing is something amateurs do.

For us intellectuals, there is something taboo-ish about writing for the desk drawer. We are heavily socialised into writing in the public domain, we are supposed to publish our manuscripts as books with academic or trade publishers, or as articles and essays in publicly available journals and magazines. Our works should not only be of the highest possible quality, but preferrably also have as wide a circulation as possible. The worst fate befalling an intellectual is to be unread by others. The quality of his/her works is secondary to their circulation and citation. It’s all about visibility and impact. That’s our destiny.

So for today’s intellectuals, writing for the desk drawer equals self-annihilation as an intellectual. And maybe it is exactly therefore that the idea of writing a memoir only for private consumption is so titillating. Rejecting the publication imperative is probably the strongest critical statement one can make about one’s social status.

From my diary, Wednesday 22 July, 1981:

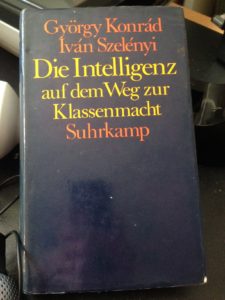

From my diary, Wednesday 22 July, 1981: Det här är en av dem. Den bidrog till att jag kunde lösriva mig från den vulgära marxism som jag hade tillägnat mig under ungdomsåren och hjälpte mig att få en mer nyanserad förståelse av det samtida klassamhället. Jag minns fortfarande, som om det var i går, när jag låg i sängen en tidig junimorgon 1979 och läste Konrad & Szelenyi med hjälp av ett tyskt-svensk lexikon och med koltrasten sjungande i bakgrunden. Fortfarande idag, nästan 40 år senare, tänker jag ibland på intelligentsian på väg till den universella makten när jag hör koltrasten sjunga.

Det här är en av dem. Den bidrog till att jag kunde lösriva mig från den vulgära marxism som jag hade tillägnat mig under ungdomsåren och hjälpte mig att få en mer nyanserad förståelse av det samtida klassamhället. Jag minns fortfarande, som om det var i går, när jag låg i sängen en tidig junimorgon 1979 och läste Konrad & Szelenyi med hjälp av ett tyskt-svensk lexikon och med koltrasten sjungande i bakgrunden. Fortfarande idag, nästan 40 år senare, tänker jag ibland på intelligentsian på väg till den universella makten när jag hör koltrasten sjunga.