In addition to Split and Splice, we have recently opened another and smaller exhibition in the reception hall — Eye Catchers and Swagger Images: Research in Poster Format (Danish: Blikfang og blærebilleder: forskning i posterformat) — with a selection of our collection of scientific posters, from the mid-1980s to the present.

In addition to Split and Splice, we have recently opened another and smaller exhibition in the reception hall — Eye Catchers and Swagger Images: Research in Poster Format (Danish: Blikfang og blærebilleder: forskning i posterformat) — with a selection of our collection of scientific posters, from the mid-1980s to the present.

The idea behind the exhibition goes back to August 2007, when we had a specialist workshop on Biomedicine and Aesthetics in a Museum Context here at Medical Museion, followed by a conference on Biomedicine and Art.

One of the speakers at the Biomedicine and Art conference was James Elkins (the Art Institute of Chicago), who spoke about the new impulses for art theory and visual studies presented by science, technology and medicine. Rikke Vindberg, who had finished her Masters degree in history and who had quite a lot of experience of exhibition making, attended Elkins’s talk and was intrigued.

Afterwards, we discussed different possibilities for applying Elkins’s ideas (especially in Visual Practices Across the University, 2007) and eventually decided to take a closer look at scientific posters, because it is an interesting hybrid form of expression between science and art.

In October 2007 we attended a medical scientific congresses in Copenhagen to get a first-hand look at a big and active scientific poster session (with many hundreds of posters) and to discuss the content and features of the posters with the scientists that had produced them.

We also wanted to acquire posters for our growing collections of contemporary biomedicine. Rikke contacted research groups at the Faculty of Health Sciences and the National Hospital (Rigshospitalet), and within a few months, she had acquired some 30 posters from different biomedical and clinical research areas, representing a variety of textual and visual expressions; the oldest from the mid-1980s

Rikke summarized her acquisition project in a 25 page curatorial report (in Danish only, unfortunately) before she left to have her first baby. But in March, when discussing how to refurbish our reception room here at the museum, the idea came up to display the poster collection. Fortunately (for the museum that is), Rikke had not yet found a new job and could therefore take on the task at once.

The result is a small, unique and fascinating exhibition. The main idea is simple. In contrast to most sci- and bio-art shows, Eye Catchers and Swagger Images highlights the aesthetic practices within science itself. The guiding idea is that all medical scientific activity, in the laboratory and elsewhere, is permeated by aesthetic practices — there is no medical science action, site or space that is not, somehow, infused with aesthetic considerations, most probably unconscious.

Scientific posters are different, however. Poster production is a lab practice which most scientists are acutely aesthetically aware about. When interviewing medical scientists in connection with the acquisitions, Rikke inquired into their aesthetic views and their choice of graphic and iconic expressions in the posters. Several of these are quoted in the exhibition.

Here’s Rikke Vindberg (right) and museum assistant Jeppe Hørring a couple of days before the show opened in late May:

Eye Catchers and Swagger Images will be open at least until early next year.

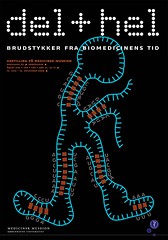

Last Thursday, we opened our new temporary exhibition Split and Splice: Fragments From the Age of Biomedicine (Danish: Del and Hel: Brudstykker fra biomedicinens tid) here at Medical Museion. In the next couple of days, we will hopefully be able to upload some images from the opening (depends on when Benny has sorted out the hundreds of pictures he took).

Last Thursday, we opened our new temporary exhibition Split and Splice: Fragments From the Age of Biomedicine (Danish: Del and Hel: Brudstykker fra biomedicinens tid) here at Medical Museion. In the next couple of days, we will hopefully be able to upload some images from the opening (depends on when Benny has sorted out the hundreds of pictures he took). We are usually covering contemporary biomedicine on display on this blog, but sometimes older stuff gets its way into this column as well.

We are usually covering contemporary biomedicine on display on this blog, but sometimes older stuff gets its way into this column as well.