My old interest in biomedical identity, individuality and personality was stimulated by an opinion piece on Buddhism and the brain by physician David Weisman in last week’s online Seed.

My old interest in biomedical identity, individuality and personality was stimulated by an opinion piece on Buddhism and the brain by physician David Weisman in last week’s online Seed.

Weisman discusses the apparent similarities between some of Buddhism’s core ideas and the alleged findings of neurology and neuroscience with respect to the non-existence of a unified ‘self’.

On this convergent view, the ‘self’ is fragmented and impermanent; what ‘exist’ are constantly changing emotions, perceptions and thoughts. The idea of a permanent, constant ‘self’ behind it is an illusion.

It struck me that this is not an uncommon view among humanities and social science scholars today. And that several influential Western philosophers — Hume, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Anscombe and Daniel Dennett — can actually be mobilised to support it. For example, Nietzsche denied the existence of a ‘self’ in On the Genealogy of Morals: “There is no ‘being’ behind doing … The ‘doer’ is merely a fiction added to the deed””.

A more recent argument against a unified ‘self’ is Derek Parfit’s suggestion, in Reasons and Persons (1984), that a stream of psychophysical events is all there is and that it is therefore unnecessary to introduce a person that has this stream of consciousness.

A more recent argument against a unified ‘self’ is Derek Parfit’s suggestion, in Reasons and Persons (1984), that a stream of psychophysical events is all there is and that it is therefore unnecessary to introduce a person that has this stream of consciousness.

The views of Nietzsche, Parfit and Buddhists evidently contradict the everyday notion of a ‘self’ (or an ‘I’, a ‘he’ or a ‘she’) lying behind ‘our’ emotions, sensations, perceptions and thoughts (‘our’ is here put in inverted commas, of course, because on this view there are no ‘we’ who ‘have’ these mental events).

But is this attack on the everyday notion of ‘self’ sustainable? Is the notion of a fragmented stream of mental events something we can actually live by? Or is the mundane notion the basis of our existance as humans?

Whatever scientific, religious and philosophical arguments can be levelled against the notion of a unified ‘self’, I believe the mundane understanding of ‘self’ is the only viable possibility.

Imagine a social world in which personal pronouns are made meaningless, a world in which it doesn’t make sense to think in terms of ‘I believe this’ or ‘you are entitled to your opinion”. A social world in which we aren’t able to think about ‘his feelings’ or about ‘her appreciation of music’. A world in which human agency, ethical responsibility, mutual trust and responsibility are all meaningless notions because there is no ‘self’ behind the stream of consciousness and gestures.

One contemporary philosopher, who systematically argues against the notion of the fragmented ‘self’ and for a more mundane understanding of ‘self’, based on close readings of ancient philosophers, is Richard Sorabji . In Self: Ancient and Modern Insights about Individuality, Life and Death (Chicago UP 2006), Sorabji claims that the ‘self’ is not an undetectable soul or ego, “but an embodied individual whose existence is plain to see”. The ‘self’ is “something that owns not only a consciousness but also a body”.

One contemporary philosopher, who systematically argues against the notion of the fragmented ‘self’ and for a more mundane understanding of ‘self’, based on close readings of ancient philosophers, is Richard Sorabji . In Self: Ancient and Modern Insights about Individuality, Life and Death (Chicago UP 2006), Sorabji claims that the ‘self’ is not an undetectable soul or ego, “but an embodied individual whose existence is plain to see”. The ‘self’ is “something that owns not only a consciousness but also a body”.

The point here is that the understanding of the notion of ‘self’ changes when we think of it in terms of the embodied individual. And I think this might give a clue to how the contemporary understanding of the ‘self’ based in recent neuroscientific findings can be interpreted in terms of a unified ‘self’ — namely that from a materialist point of view it doesn’t make sense to think in terms of a fragmented and impermanent ‘self simply because the material basis of the neuroscientific ‘self’ is a series of signalling processes among a permanent set of interconnected neurons.

One of their recent hot topics is plastic pollution of the oceans. All oceans, especially the North Pacific, contains millions of tons of discarded man-made plastic items. They are largely non-biodegradable, which means they will only disappear slowly through physical wear — which can take many decades for a plastic bottle.

One of their recent hot topics is plastic pollution of the oceans. All oceans, especially the North Pacific, contains millions of tons of discarded man-made plastic items. They are largely non-biodegradable, which means they will only disappear slowly through physical wear — which can take many decades for a plastic bottle.

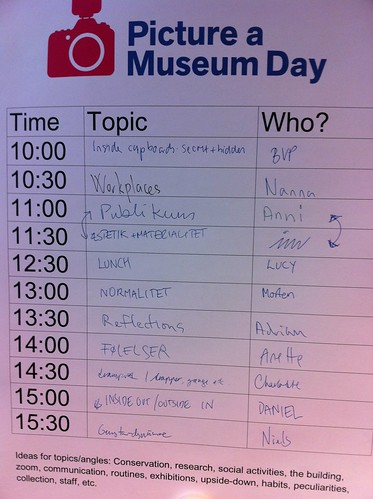

We’re pretty proud of being the fourth most energetic contributor to Flickr and Twitter’s joint

We’re pretty proud of being the fourth most energetic contributor to Flickr and Twitter’s joint

My old interest in biomedical identity, individuality and personality was stimulated by an

My old interest in biomedical identity, individuality and personality was stimulated by an