The programme for the 5th European conference of The Society for Literature, Science and Arts (SLSA) in Berlin, 2-8 June—on “Figurations of Knowledge”—is now available on-line.

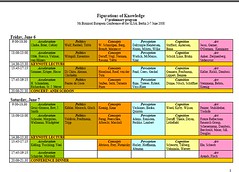

The programme committee has not only put together an unusually rich, varied and exciting carneval of presentations which (in my humble opinion) leaves the usual social studies of science meetings organised by EASST and 4S in the desert of oblivion. It has also developed its own colour-happy program aesthetics:

Anyway, it’s not for coloro-political reasons that Medical Museion is participating with/in two sessions:

On Wednesday 4 June, Jan Eric Olsén is organising a session titled “Recent Biomedicine and Vitality” with papers by Sniff Nexø (“A matter of disposal: Enacting aborted foetuses in hospitals”), Hanne Jessen (“Vitality of a scientific model: The coming into being and trajectory of a new laboratory animal”), Susanne Bauer (“Risk assessment software and the biopolitics of prevention”), and himself (“Life struggles and the invaded body”). See their abstracts here.

Two days later, on Friday 6 June, I will give my paper on “Five (good and bad) reasons why a medical museum director wants to bring art and science together” in the session “Rethinking Representational Practices in Contemporary Art and Modern Life Sciences”, organised by Ingeborg Reichle.

There is a plethora of tickling offers on this year’s program and we are in heavy competition for hundreds of SLSA souls. (Not to mention the sad fact that one of the papers I’d really love to hear, viz., Matthias Bruhn‘s “Life in layers. Art history of microtome”, is simultaneous with my own talk :-). That aside, the SLSA meeting in Berlin promises to become the event of the year for all science, technology and medical museum faculty or staff members who wish to expand their horizon. Dead-line for registration (details here) is 30 April.