A collection of videodocumentaries of art projects that implement contemporary technologies of artificial life, robotics, and bio- and genetic engineering has just opened in the Kaliningrad branch of the Russian National Centre for Contemporary Arts.

The exhibition — curated by Dmitry Bulatov under the title ‘Evolution Haute Couture: Art and science in the post-biological age’  — contains a row of interesting works including, for example, Floris Kaayk’s ‘Metalosis Maligna’, “a fictitious documentary about a spectacular yet chronically disabling disease which affects patients who have been fitted with medical implants” (quote from here).

— contains a row of interesting works including, for example, Floris Kaayk’s ‘Metalosis Maligna’, “a fictitious documentary about a spectacular yet chronically disabling disease which affects patients who have been fitted with medical implants” (quote from here).

Bulatov (who has some interesting views on art and biotech) takes a broad sweep over contemporary and future biomedicine and biotech:

- Artificial but Actual (Artificial Life)

- Limits of Modeling (Evolutionary Design)

- Shining Prostheses (Robotechnics)

- Body as Technology (Technobody modification, WearComp, Biomechatronics)

- More than a Copy, Less than Nothingness (Bio-and Genetic Engineering)

- Semi-Living (Tissue Engineering)

- Post-Sodom and Post-Gomorrah (Nanoengineering)

from the following perspective:

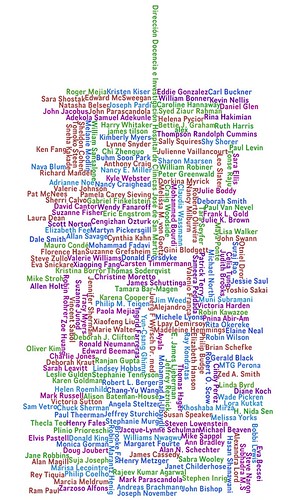

What is radicalization and redundancy of technological and scientific progress? What is the evolutionary potential of the basic technological trends of the XXI century – robotics, bio-and genetic engineering, nanotechnology – like? Each of these trends actualize the traditionally formed boundaries of beginning and end of human existence, the demarcation of norm and pathology and the distinction of the non-(or semi-)organic model or entity. These – and many other issues – cannot be taken into consideration without the experience of contemporary techno-biological arts; the representatives of which do not so much confirm the technological versions of contemporaneity, as determine their boundaries. Art that is created under the new conditions of postbiology – under the conditions of an artificially fashioned lifespan – cannot help but take this artificiality as its explicit theme. However, time, duration, and life cannot be shown directly but only as documentation. The dominant genre of postbiological art is thus technological documentation: plans, drafts, and videos. It is precisely at this point where documentation becomes indispensable, and produces the life of the living thing: the documentation inscribes the existence of an object in history, and gives the object a lifespan which this existence (independent of whether this object was ‘originally’ living or artificial).

More on the art centre’s website and here. Looks like a good occasion to take a closer look at Kaliningrad (direct flights with Rossiya-Russian Airlines from Copenhagen for about 1500 DKK = approx. 300 USD).

(thanks to Ingeborg for the tip)

Take CT scanners for example: huge white or light blue plastic/metal boxes, that’s all.

Take CT scanners for example: huge white or light blue plastic/metal boxes, that’s all.

In addition to the presentation and discussion of work-in-progress, the group will serve as a forum for discussion of issues of common interest, such as the identification and development of source materials; the uses and pitfalls of oral histories in research; and collaborations between historians and the biomedical community.

In addition to the presentation and discussion of work-in-progress, the group will serve as a forum for discussion of issues of common interest, such as the identification and development of source materials; the uses and pitfalls of oral histories in research; and collaborations between historians and the biomedical community. Here’s the audience gathering for the session on ‘The Public Engagement of Science and Web 2.0’ organised by Gustav Holmberg for the

Here’s the audience gathering for the session on ‘The Public Engagement of Science and Web 2.0’ organised by Gustav Holmberg for the