Are you a fox or a hedgehog?

The folkish distinction between the two personality types can be found already in a text fragment from the Greek poet Archilochus, who flourished around 650 BC:”A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog one important thing”.

Like so much else from classical Greek literature, Archilochus’ proverb became popular in the Renaissance. In Adagia (see the full text here), Erasmus of Rotterdam gave the Latin version of it as “Multa novit vulpes, verum echinus unum magnum”.

In our time, the dichotomy was again popularised by philosopher Isaiah Berlin. In The Hedgehog and the Fox (1953), Berlin distinguishes between human beings “who are fascinated by the infinite variety of things and those who relate everything to a central, all-embracing system.” (quote from here).

In our time, the dichotomy was again popularised by philosopher Isaiah Berlin. In The Hedgehog and the Fox (1953), Berlin distinguishes between human beings “who are fascinated by the infinite variety of things and those who relate everything to a central, all-embracing system.” (quote from here).

Most of my academic friends and colleagues over the years have been hedgehogs. They have stayed with the same academic discipline throughout their career and focused on a rather small set of problems, which they have circled around for years and decades, often with a large number of publications. They have produced comprehensive textbook articles and regularly been invited as keynote speakers to conferences to lecture on the state of the art in their fields.

I am definitely not a hedgehog. I have moved between several disciplines — from biology in the late 1960s, to the history and sociology of the intelligentsia in the 1980s, to the history of science/medicine in the 1990s, to museum studies in the 2000s — and I have also jumped from topic to topic within the discipline: as a historian of science I worked on the rise of ecology in Sweden, on the history of 20th century immunology, on scientific biography as a genre, etc.

Thus I have been working on shell formation in ectoprocts (my research topic in 1967-1969), on the use of cladistics in molecular evolution (1969-1971), on the history and sociology of intellectuals (1978-late 1980s), on the history of ecology (1977-1986), on the class structure in the information society (1982-mid 1980s) on the history of immunology (1990s), on new scientometric methods, on the life and work of the immunologist Niels K. Jerne, on studies in scientific biography (late 1980s-mid 2000s), and on collecting and display of contemporary science in museums (2006-2014).

I have actually done substantial work in all of these fields, publishing the results in peer-reviewed international scientific journals and so forth. In several of these fields I was a recognised expert, in some even a leading expert (and in at least one small field I am still the world expert).

But I never had the enduring passion (or patience) to remain within a single research field. As soon as I had marked my territory — by writing a couple of articles or a book, or edited an anthology — I went on to another field. There was always something more exciting, something more important, somewhere else. I never shifted abruptly; there was usually an overlap of one to several years when I worked in both fields simultaneously. But ultimately I always jumped on to something new.

Being an intellectual fox is a mixed blessing. On the positive side: you never get bored, you meet new and exciting scholars and learn something new all the time. It is always fresh territory. You become a kind of polymath (polyhistor).

The negative side of being an academic fox is that you feel you never get to the bottom of things. You never really master a whole academic field; you never get the chance to play the role of a grand old man in the field; you will never receive a Sarton medal (even if you had been as clever as the actual recipients).

Also, being a fox you make few academic friends of the kind that Aristotle describes as ‘accidental’, i.e., based on pleasure and utility. On the other hand, it might be easier to cultivate Aristotle’s third kind of friendship — that between people who are good and alike in virtue — because you are neither competing with nor utilising each other.

Isaiah Berlin once said he did not really take the fox-hedgehog dichotomy very seriously, telling his biographer that the title of the book was almost a joke. But even if we accept the dichotomy — and I think one shall take seriously adages that have survived since classical antiquity — the distinction is only ideal typical. I am not a fox 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I have hedgehogianic bouts as well, at least for shorter periods of time.

What makes the distinction interesting for my study of autobiography is not only that it apparently provides a neat summarising label for my life’s intellectual journey, but also that it draws my attention to other aspects of my life, where I seem to have displayed the same kind of behaviour. For many years I was an idealtypical fox in my private life as well, jumping from one relation to another and moving from one place to the other. Also with respect to cultural taste have I been serially promiscuous. (Politically, I have been pretty stable though.) Only now, towards the end of my life, I realise how great it is to live in one place and in a long-term stable relationship. So perhaps foxes turn into hedgehogs with age? Or maybe I have always been a hedgehog in fox disguise?

To what extent do such simple personality labels have a place in autobiographical writing? Are they common? Helpful? Too simplified? Misleading? Or is there, in spite of Berlin’s joking attitude, an ancient and uncontestable truth behind such labels? I will get back to this question in later posts.

A link to this post was published on Facebook 17 december 2015 and gave rise to a number of comments:

Read More

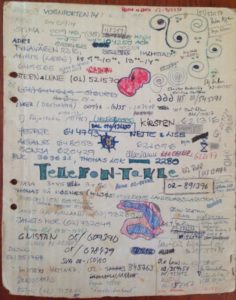

Question for my friends – when it comes to personal things, do you keep them for the future or do you throw them away after a while? And do you treat documents, books, images, and material stuff differently?

Question for my friends – when it comes to personal things, do you keep them for the future or do you throw them away after a while? And do you treat documents, books, images, and material stuff differently?