Today, Ken Arnold is starting his temporary appointment as Visiting Professor in Medical Science Communication and Museology at Medical Museion.

When he is not visiting Medical Museion, Ken Arnold heads the Public Programmes team at the Wellcome Trust, where his role is to creatively direct Wellcome Collection — a very successful public venue in London that seeks to explore the connections between medicine, art and life. It has received very positive press attention throughout the world, attracted over 300,000 visits per year since 2007, and has been nominated for the Museum of the Year and European Museum of the Year awards.

When he is not visiting Medical Museion, Ken Arnold heads the Public Programmes team at the Wellcome Trust, where his role is to creatively direct Wellcome Collection — a very successful public venue in London that seeks to explore the connections between medicine, art and life. It has received very positive press attention throughout the world, attracted over 300,000 visits per year since 2007, and has been nominated for the Museum of the Year and European Museum of the Year awards.

The Wellcome Collection has emerged as the culmination of 15 years of innovative public work at the Trust, where Ken Arnold has run a variety of arts and exhibitions activities, including a gallery at the Science Museum devoted to exploring medicine in context. He also co-ordinated the establishment of the Wellcome Trust’s arts funding initiatives, which support collaborative work between scientists and artists. He was also Chief Curator of the highly successful exhibition Medicine Man: the Forgotten Museum of Henry Wellcome shown at the British Museum in 2003.

Ken Arnold gained a B.A. in Natural Sciences at Cambridge University and a Ph.D. in the history of science from Princeton University, and worked in a variety of museums (national and local) on both sides of the Atlantic, before joining the Wellcome Trust in 1992. He regularly writes and lectures on the culture of museums past and present and on the contemporary relations between the arts and sciences.

Some of his articles in collected volumes are highly original contributions to the problem of how to use art in the presentation of medical science. Other articles have raised the problems of the relation between history of medicine and medical museums in new and fruitful ways.  In the monograph Cabinets for the Curious: Looking Back at Early English Museums (2006), Arnold draws on the historical experiences of the classical 16th and 17th century curiosity cabinet as a resource for opening up a new field of discourse for contemporary museum innovation. The Collector’s Voice: Critical Readings in the Practice of Collecting (2000) raised new issues about the role of collecting in the history of museums. His academic activities also include supervision and examination of PhD-projects in science communication and museums studies at the University of Leicester, Leeds Metropolitan University, Oxford University and Open University.

In the monograph Cabinets for the Curious: Looking Back at Early English Museums (2006), Arnold draws on the historical experiences of the classical 16th and 17th century curiosity cabinet as a resource for opening up a new field of discourse for contemporary museum innovation. The Collector’s Voice: Critical Readings in the Practice of Collecting (2000) raised new issues about the role of collecting in the history of museums. His academic activities also include supervision and examination of PhD-projects in science communication and museums studies at the University of Leicester, Leeds Metropolitan University, Oxford University and Open University.

We are very happy to get this opportunity for close encounters with Ken Arnold and thereby draw on his long experience in research-based exhibition making. If anyone wants to meet him during his Copenhagen sojourn, please contact him at k.arnold@wellcome.ac.uk.

(image credit: LabforCulture, www.labforculture.org)

Donna Bilak’s review of Frances Larson’s An Infinity of Things: How Sir Henry Wellcome Collected the World (Oxford UP, 2009) points to an interesting contradiction in Larson’s book — is it a biography of the collection or of the collector?

Donna Bilak’s review of Frances Larson’s An Infinity of Things: How Sir Henry Wellcome Collected the World (Oxford UP, 2009) points to an interesting contradiction in Larson’s book — is it a biography of the collection or of the collector?

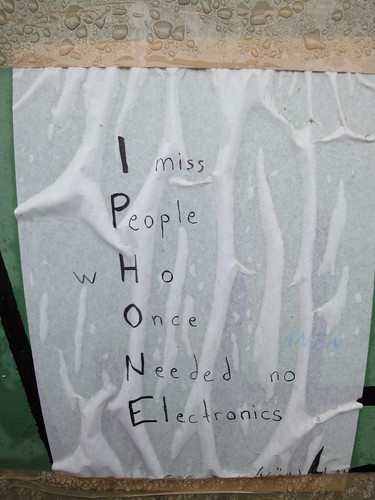

Despite Rosen’s focus on the legal aspects of our eternal exposure on the web, the most interesting aspect of the article is his discussion about the emergence of new social norms regulating our online presence. He has actually “been at dinners recently where someone has requested, in all seriousness, ‘Please don’t tweet this’”.

Despite Rosen’s focus on the legal aspects of our eternal exposure on the web, the most interesting aspect of the article is his discussion about the emergence of new social norms regulating our online presence. He has actually “been at dinners recently where someone has requested, in all seriousness, ‘Please don’t tweet this’”.

In the monograph

In the monograph