De sidste par måneder har vi som sagt været igang med at formulere en ansøgning om penge til udvidelse og videreudvikling af Medicinsk Museion.

Videreudviklingen går ud på at vi skifter identitet, fra primært at være et medicinsk-historisk museum, til at blive et museum, der mere generelt handler om mennesket i sundhed og sygdom.

Formålet med det udvidede museum er at fremme forståelsen af sundhedsforskningens og sundhedssystemets udvikling og betydning for samfundet og det enkelte menneske — ved at sætte den aktuelle forskning og teknologiske udvikling på sundhedsområdet ind i et bredt historisk, kulturelt og eksistentielt perspektiv.

Det er meningen at det udvidede museum skal engagere forskere, studerende, virksomheder og organisationer på sundhedsområdet til kreativ dialog med borgerne om den videnskabelige og teknologiske udvikling, dens drivkrafter og konsekvenser. Vi har også ambitionen at involvere brugerne som medproducenter af den medicinske kulturhistorie for at stimulere til fælles ansvar for den fremtidige videnskabelige og teknologiske udvikling.

Den udadrettede virksomhed skal, ligesom nu, tage udgangspunkt i vores egen forskning (på højt internationalt niveau som det hedder i dansk universitetsjargon) for at skabe ny viden om sundhedsforskningens og sundhedssystemets fortid og nutidshistorie — for dermed at bidrage til formuleringen af mulige fremtidsscenarier på sundhedsområdet.

En væsentlig forudsætning for det udvidede museum er Københavns Universitets enestående medicinhistoriske samlinger. Men museet vil også drage fordel af den stærke humanistiske og

samfundsvidenskabelige forskning om sundhedssystemet som bedrives ved Københavns Universitet og andre universiteter i regionen. Og vi håber at det udvidede museum vil få en stærk position i kraft af samarbejde med sundhedsforskningsmiljøer, hospitaler og farma-/medikotekniske virksomheder i Øresundsregionen.

Ved at kombinere egen humanistisk forskning, kulturhistoriske samlinger, der spænder over tre århundreder og et formidlingsarbejde, som inddrager en række ideer inden for museum 2.0, tror vi at vi kan være langt fremme med at sætte dagsorden for, hvordan videnskabs-, teknologi- og medicinske museer skal fungere i fremtiden.

(mere om planerne følger)

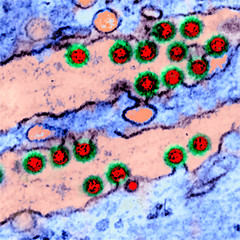

Anyone with the slightest interest in the history of virology and visualizations of viruses will enjoy

Anyone with the slightest interest in the history of virology and visualizations of viruses will enjoy