When I was a kid I loved to play board games of all kinds (and hated to lose). But I don’t think I ever encountered any medical games. Turns out there are quite a few of them, however, some of which are probably best described as educational games.

Operation (1965) is a battery-operated game for kids from age 6 and older.  In Medical Monopoly (1979) you play a doctor running a hospital, and if you are skilled at diagnostics and spending your funds wisely on acquiring the right kinds of drugs, organs for transplants, etc., you’ll get more patients.

In Medical Monopoly (1979) you play a doctor running a hospital, and if you are skilled at diagnostics and spending your funds wisely on acquiring the right kinds of drugs, organs for transplants, etc., you’ll get more patients.

What’s peculiar about Medical Monopoly — a game which allegedly is used by some school districts in the US to teach health care — is that the winner is the player who first fills the hospital with patients. Common sense would give credit to the player who first empties the hospital. But maybe the game only reflects medical hospital profit system business as usual, in which case it’s a pretty realistic training ground for living in the US.

Then I just found out (thanks to Jessica for the tip) about yet another medical educational board game. Contrary to most games Pandemic isn’t competetive, but co-operative. The players are supposed to help each other control outbreaks of diseases around the world and search for cures against them. If you play badly and don’t co-operate well, the diseases will win!

Then I just found out (thanks to Jessica for the tip) about yet another medical educational board game. Contrary to most games Pandemic isn’t competetive, but co-operative. The players are supposed to help each other control outbreaks of diseases around the world and search for cures against them. If you play badly and don’t co-operate well, the diseases will win!

Jessica believes Pandemic could be used for serious educational purposes because it “does a really nice job of challenging players to effectively distribute resources and minimize losses in an unpredictable milieu”:

Players end up debating various tactics and strategies several turns in advance: for example, is it better to dispatch your scientist to a relatively remote but heavily infected area to prevent an imminent outbreak, or have her stay close to a research station to effect a cure? It all depends, since the game has mechanisms built in to keep things unpredictable while mimicking how epidemics of infectious disease can rapidly build on themselves and spiral out of control. Just as in real life, you’ll lose pretty quickly if you try to treat every single infection – you have to choose your battles and concentrate on long-term damage management. Because of that, I found myself wondering whether the game would work in a high school or college course dealing with public health policy, and decided it might – except it’s almost too difficult! (But then, so is public health policy).

Maybe it’s not advanced enough for students at the public health programme here at the University of Copenhagen — but on the other hand designing a more advanced epidemiological board game would be an excellent topic for a Bachelor’s thesis in public health.

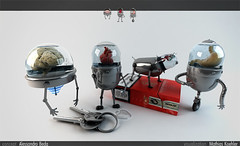

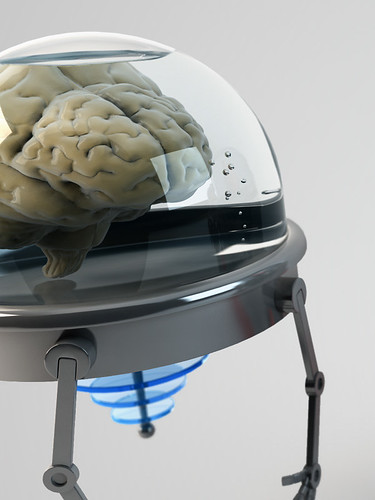

Her er yderligere medicinsk-inspireret legetøj til vores kommende butik — Matthias Köhler’s og Alessandro Beda’s “The Little Robots”: “Each robot features a glass tank with some floating organs”. Den perfekte fødselsdagsgave til familjen 10-årige nørd (ihvertfald inden friværdierne er helt spist op — de nuttede små kryb koster nok kassen). Vi må få gang i den butiksidé inden 2012.

Her er yderligere medicinsk-inspireret legetøj til vores kommende butik — Matthias Köhler’s og Alessandro Beda’s “The Little Robots”: “Each robot features a glass tank with some floating organs”. Den perfekte fødselsdagsgave til familjen 10-årige nørd (ihvertfald inden friværdierne er helt spist op — de nuttede små kryb koster nok kassen). Vi må få gang i den butiksidé inden 2012.

Sounds to me like a great vision for the future of public engagement with the humanities. And not at all unrealistic, because a precedent has already been set — by a science journal.

Sounds to me like a great vision for the future of public engagement with the humanities. And not at all unrealistic, because a precedent has already been set — by a science journal. In

In  Then I just found out (thanks to

Then I just found out (thanks to