Learning new software tools takes a lot of time, so I always take the opportunity to learn some basic tricks by looking over the shoulders of my colleagues while they handle the interface. But often my colleagues are as unknowledgeable as I am. The obvious solution then is video tutorials. There are thousands hundreds of them if you want to learn Photoshop or how to create your WordPress blog and so forth. But I haven’t seen any specialized service for biomedical researchers before. Now Bioscreencast has created a video tutorial library where you can watch (presently 128) videos that tell lots of useful stuff — for example, I just learned how to create a RSS feed for continuously showing PubMed search results on my customized ig-Google page. Nifty!

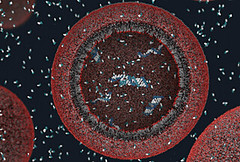

Last week Nature carried a fascinating advance online article* written by a research group at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) lead by Jack Szostak. They have created a simple artifical protocell in the form of a single-stranded DNA-template within a shell of such fatty acids that were likely to have been present in early life environments four billion years ago.

It turned out that this particular protocell could take up nucleotides from the outside without the help of ‘modern’ protein pores and channels and that these molecules then took part in the template-copying reaction. In other words, a precursor to a simple artificial life system. Read more here.

It turned out that this particular protocell could take up nucleotides from the outside without the help of ‘modern’ protein pores and channels and that these molecules then took part in the template-copying reaction. In other words, a precursor to a simple artificial life system. Read more here.

This is great stuff for everyone who is fascinated by the problem of the emergence of early life (and the construction of artificial life). But equally fascinating is the fact that this research is conducted by a group of scientists at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Mass General Hospital. This tells something about the open-minded research strategies of these two medical research institutions — a far cry from the narrow understanding of medical research (and research in general) which the Danish government and its research authorities have adopted over the last decade under the slogan ‘Fra forskning til faktura’ (from research to invoice).

I doubt that scientists in a Danish medical research institution (not even to think of a hospital) would survive for long if they focused their research efforts on the origin of life. Because even though such research may be very important for the understanding of cell functions in the long perspective, there is no immediate medical payoff; no cure for cancer or Alzheimer’s in sight whatsoever.

*S. Mansy et al., “Template-directed synthesis of a genetic polymer in a model protocell”, Nature online 4 June 2008.

After the minisymposium with Jens Hauser and Sepp Gumbrecht on the concept of ‘presence’ here at Medical Museion last spring, our research group has repeatedly come back to the relation between mediated visualizations of biomedical objects, on the one hand, and the immediacy of touching them, on the other (see, for example, Jan Eric’s earlier post on Condillac’s statue).

As an anecdotal illustration of the immediacy of touch, I’d like to present the following personal experience.

In mid-March, I accompanied my partner to the National Hospital here in Copenhagen for an ultrasound scan of our then 13 week old foetus. As thousands of other prospective parents we were of course thrilled by what we saw on the screen:

Watching our future baby ‘live’ on a computer screen like this was quite amazing, even though we had seen such pictures on the internet before. It’s an experience we share with millions of others: digitalized ultrasound scanning foetus images have become an integral part of the contemporary understanding of what it means to deliver new citizens to the world. A striking image of early life that is easily communicated in our visual culture and as such an illustration of the formation of biocitizenship, both discursively and substantially.

Back to the anecdote: Six weeks later, we went for the second screening and watched the same kind of picture, just more detailed, with ears, fingers, toes and everything. It was, of course, very satisfying to see that the pregnancy proceeded well, and that there was no need to worry.

Yet, none of us were really moved by the experience. And I realised that even though I had been quite amazed during the first scanning session in March, both sessions left me somehow unsatisfied. There was something lacking which I couldn’t really articulate. My partner felt the same way, especially after the second scanning.

It was no big thing, and none of us found it wortwhile discussing it at length. For my own part, I shrugged it off as one of these many moments of distraction that acompany academic life.

However, two weeks after the second scanning, my partner suddenly said one evening: ‘put your hand on my belly’. I did — and there it was: the ‘rumbling’ that I had read about! Something moving inside. Not really kicking, but ‘rumbling’.

Wow! Double wow! This was our baby, no doubt. I couldn’t see it, of course, and I couldn’t distinguish arms, legs or head from each other. It was just a ‘rumbling object’ deep inside my partner’s belly.

From a medical point of view my subjective haptic experience was of course nothing compared with the detailed, objective and communicable ultrasound visualizations. And yet — as an experience of emerging life it was much more evocative. Touching our ‘rumbling’ foetus made a much stronger impression on me than seeing him/her (we don’t want to know ‘its’ sex yet) in high screen resolution. Now he/she was real — for real!

And then I understood why the two previous scanning sessions had left us somewhat unsatisfied, as if something was lacking. Despite all the exquisite visual detail, the perception of a scanning image is mediated. That is, there is literally a medium between the perceiving spectator and the foetus. In this case, a technically sophisticated clinical platform — an obstetric clinic with trained technicians operating state-of-the-art ultrasound echoprobe equipment according to standardized procedures and with the newest imaging software, etc. — stand between us and the foetus. While my hand on her belly is unmediated (unless you want to call the belly muscles and the placenta a ‘medium’).

As an anecdote this has rather limited evidential value, agreed. But it nevertheless makes me think about the immediacy of touch, and to what extent the sense of touch is an undervalued sense in a world which is dominated by the sense of vision (and partly the auditory sense). (For further views on this, see Jan Eric’s and my paper to the ‘Artefact’ meeting in Oslo last September.)

It also raises questions about touch as a basic cognitive sense (cf Jan Eric’s post on Condillac), about touch as an emotionally loaded sense, about the communicability and possibility for shared cultural experiences of touch, and so forth. Lots of questions for later posts.

(finally, to medical doctors reading this post: I’m not at all against imaging technologies, of course; I’m just fascinated by the relation between visual mediation and the immediacy of touch 🙂

As you may have noticed, this blog has a crush on microarray technology, both as a social and political phenomenon (see here) and as an object of display (see here and here).

As you may have noticed, this blog has a crush on microarray technology, both as a social and political phenomenon (see here) and as an object of display (see here and here).

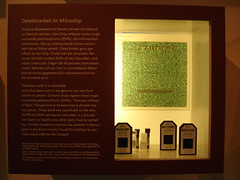

Therefore – congratulations to the Berliner Medizin-historisches Museum for being the first museum (as far as I know) to display microarrays in a permanent exhibition.

It’s just one small showcase in the new permanent exhibition ‘Dem Leben af der Spur’ [On the track of life] which opened last October. The text is short and probably pretty unintelligible to non-experts, and the displayed Affymetrix® chips are not contextualized, neither historically, nor socially or politically. Nevertheless, here they are — the first gene chips in a permanent museum exhibition.

I’ll be back with a review of the exhibition as a whole.

Yesterday morning, before our session on art and science, I took a walk through the beautiful old Charité area — now one of the joint medical campuses of Humboldt Universität and Freie Universität — with 19th and early 20th century buildings spread out in a large park.

Yesterday morning, before our session on art and science, I took a walk through the beautiful old Charité area — now one of the joint medical campuses of Humboldt Universität and Freie Universität — with 19th and early 20th century buildings spread out in a large park.

When I passed by one of the buildings that houses some of the veterinary medical departments, an aluminium-box to the right of the entrance caught my eye.

Went closer and discovered a small handwritten red label on the front of the box:

‘Refrigerated samples (4o)

Institute of Virology’

Apparently it’s a refrigerated drive-in (or walk-by) virus sample delivery box:

I asked a man who was standing smoking outside the building to open the lid to demonstrate how it works:

My anonymous assistant had no attachment to the veterinary virology department, so he couldn’t really explain how the box is (was) used. What kind of samples are (were) delivered here? By whom? A night-delivery box? What kinds of tests? And how does (did) the sender get the information back? Is (was) it a foot-and-mouth disease sample emergency delivery box?

And then I saw that someone has glued a green label below the official one:

‘bürgerinitiative / rettet die fleischerei’ (‘citizen initiative / save the butcher-shops’).

One of these witty anti-establishment micro protests and art installations which has made the Berlin autonomous movement world famous. Perhaps a vegan tongue-in-cheek criticism of a food industry which would be in serious trouble if institutes of virology weren’t producing knowledge that kept animals alive for later slaughter and sale.

A nice item for acquisition if we were a museum responsible not only for human medicine but also for understanding and displaying veterinary medicine as well.

After today’s SLSA afternoon sessions I walked down Luisenstrasse through the Humboldt University medical campus (Charité) and suddenly saw this poster hanging on a fence:

After today’s SLSA afternoon sessions I walked down Luisenstrasse through the Humboldt University medical campus (Charité) and suddenly saw this poster hanging on a fence:

“Are you doing research? Do you want to know more about several biomedical topics? Join this year’s conference and discuss your results with students from all over the world …”

The poster invites passersby to the 19th European Student’s Conference — an event which has taken place at Charité since the fall of the Berlin Wall — one of many East-West reunion activities.

Why am I so fascinated by this little poster? It’s an example of biomedicine on display, yes — but there is more to it. I guess it has something to do with how the biomedical world enters the urban street space and becomes part of our everyday poster display experience, like street announcement of concerts and theatre performances. Isn’t that what they mean by the formation of biocitizenship?

Forget about designing your own animals, molecules, cells and labware on powerpoints. A company called Motifolio (I assume there is a host of similar companies out there) provides an array of custom shapes of biomedical objects: the whole mount of 700 scalable and editable clips costs 149 USD.

Forget about designing your own animals, molecules, cells and labware on powerpoints. A company called Motifolio (I assume there is a host of similar companies out there) provides an array of custom shapes of biomedical objects: the whole mount of 700 scalable and editable clips costs 149 USD.

Nifty — but like other standardized images and customised power point presentations they will probably become tiring after a while. Isn’t there an emerging blackboard retro movement?

Nifty — but like other standardized images and customised power point presentations they will probably become tiring after a while. Isn’t there an emerging blackboard retro movement?

The medical faculty at the University of Oslo has announced a full/associate professorship in medical history, with a focus on Norwegian history. The candidate shall have a research background in Scandinavian/Norwegian medical history, which sort of narrows the field of possible applicants. Read more here. Deadline for applications is already 1 August 2008.

A few minutes ago — as I was sitting in my beautiful and quiet room in Schokofabrik (the best B&B in Berlin), struggling with my paper on art and science in medical museums for the SLSA-session on Friday — a mail dropped in announcing a lecture by science writer Phillip Ball on Thursday 10 July, which may be quite interesting for us in the medical museum business.

Phillip Ball lecture is occasioned by his receipt of the 2007 Dingle Prize for communicating the history of science and technology through his book Elegant solutions: Ten Beautiful Experiments in Chemistry (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2005):

Scientists frequently talk about ‘beauty’ in their work, but rarely stop to think quite what they mean by it. What makes an experiment beautiful? Is it the clarity of the design? The elegance of the apparatus? The nature of the knowledge gained? There have been several recent attempts to identify ‘beautiful’ experiments in science, especially in physics. But Philip Ball argues that, not only is chemistry often neglected in these surveys, but it has its own special kinds of beauty, linked to the fact that it is a branch of science strongly tied to the art of making things: new molecules and materials, new smells and colours (my emphasis)

The making of new molecules and materials, smells and colours isn’t restricted to chemistry, of course. Same with biotechnology, tissue engineering, etc. The beauty of, say, a new bladder tissue should then lie, pace Bell, in its new materiality, smells and colours. Good point. Must read the book!

The Royal Institution, 21 Albemarle Street, London, at 7pm

(thanks to Patricia for the mail).

PS to last post: don’t miss the Medical Museion/’Biomedicine on Display’-born session “Recent biomedicine and vitality” on Wednesday 4 june at 15.45-17.15 in the Virchow-Raum, Langenbeck-Virchow-Haus. The session is chaired by Jan Eric Olsén and contains the following papers:

- Sniff Andersen Nexø: A matter of disposal: Enacting aborted foetuses in hospitals.

- Hanne Jessen: Vitality of a scientific model: The coming into being and trajectory of a new laboratory animal.

- Susanne Bauer: Risk assessment software and the biopolitics of prevention.

- Jan Eric Olsén: Life struggles and the invaded body.