I’ve rarely given fiction high priority

I think fiction – poetry, novels and especially short stories – is an important dimension of human culture. I believe those who suggest that reading fiction is an essential element of Bildung. I’ve always told my science and medical students to expand their worldview by reading outside their narrow professional field.

But I haven’t lived as I’ve been teaching others. True, I’ve never dismissed fiction, but I’ve never perceived myself an educated reader and I’ve rarely given fiction high priority in my own life.

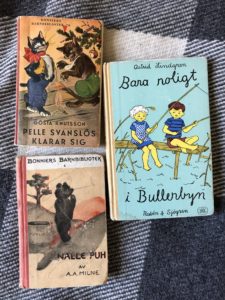

I learnt to read early, probably when I was five. I remember my favourites were Gösta Knutsson’s stories about Pelle Svanslös (Peter No-Tail), A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Poo (Nalle Puh), Astrid Lindgren’s early novels about Pippi Långstrump (Pippi Longstocking) and the kids in Bullerbyn (The Children of Noisy Village). I also remember reading Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Jules Verne’s Två års ferie (Deux ans de vacances). I still have some of these gems in my bookcases.

I continued to read voraciously in my pre-teens; I remember borrowing 10-15 books a week from the local library at Medborgarplatsen in Stockholm; mainly popular science of course (I loved reading about dinosaurs), but also some fiction, including Enid Blyton’s Famous Five (Fem-böckerna), W. E. Johns’ books about the WW-II pilot Biggles, and Alexandre Dumas’ d’Artagnan-romances. I loved Jules Verne’s realistic adventure stories (Vingt Mille Lieues sous les mers, Voyage au centre de la Terre, L’Île mystérieuse, and so forth), which I read over and over again in abridged Swedish translations.

During the high school years, however, my omnivorous interest in fiction literature waned. We read a lot of Swedish literature – books by Werner von Heidenstam, Pär Lagerkvist, Eyvind Johnson, Harry Martinsson, Nils Ferlin, and (the Danish) Martin A Hansen – but I’m afraid all this obligatory high school reading killed my literary interests. I engaged more with authors I had found on my own, like Herman Hesse; I still remember reading Das Glasperlenspiel (in German) on a train ride from Stuttgart to Stockholm.

My youthful good reading habits never came back. During my history of science career in the 1970s through 1990s, I read very little fiction, and almost no poetry. When I went through the bookcases the other day to reconstruct my reading history, I found Göran Tunström’s Juloratoriet (The Christmas Oratorio), Ceslaw Milosz’ The Issa Vally, and copies of books by Camus, Canetti, Kundera, Konrad, and Kafka on the shelves, as well as Montaigne’s and Orwell’s essays. At some point in the late 1990s I also seem to have fallen in love with poet Andrew Motion. But these are isolated items among thousands of scholarly volumes on history, sociology, political science, literary theory, biography, ethics, and general humanities and social science topics that otherwise fill my bookcases.

The exception to this general lack of interest in fiction was occasional bouts of binge reading. I had a period in the mid-1990s when I suddenly felt I knew nothing about classical literature and spent a couple of months with Dante, Milton, the unabridged Robinson Crusoe, and Shakespeare’s Richard III, The Tempest, King Lear, Macbeth etc. in critically commented editions (sometimes complemented by recordings of the plays with John Gielgud and the young Kenneth Branagh). And when I read classical Greek in 1997-99 I plowed through the parallel Greek-English versions of Homer, Sophocles and Aristophanes (I especially liked Kenneth Dover’s critical edition of The Frogs, in which the commentary fills four times as much as the play!). I seems like I preferred the philological analysis of the texts more than the immediate aesthetic appreciation of them.

I did occasionally read for aesthetic and emotional reasons, however. After my divorce in 2002, I found some consolation in binge-reading Ian McEwan and A. S. Byatt, and particularly in Anita Brookner’s gloomy novels about spinsters and lonely elderly widowers (I read all of them, very depressing stuff!). I’ve also devoured hundreds of volumes of Nordic crime fiction — Henning Mankell, Håkan Nesser, Kristina Ohlsson, Arnaldur Indridason, Viveca Steen, and Åsa Larsson, but only a couple of chapters of Camilla Läckberg — during my summer vacations in the 2000s. And while we had separate bedrooms for a while after my youngest son was born in 2011, I read a fair amount of Murakami’s novels and short stories (I vividly remember long nights in bed alone with 1Q84).

I’m very aware of all the new fiction literature I ought to read to become a really educated old man. My partner subscribes to literary magazines and reads at least a new novel every month – but I rarely come across a work of fiction that steals my heart. The never-ending outpour of new Man Booker Prize winning novelists leaves me cold. I’ve tried some of them, for example Jonathan Franzen, but I find him and many other contemporary authors too verbose; I prefer the precise, almost clinical, prose of J. M. Coetzee, but there doesn’t seem to be many good authors of that kind.

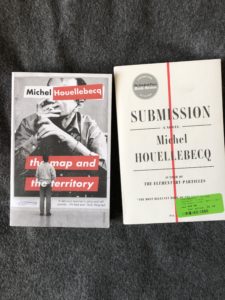

The only recent exception to my current lack of interest in fiction is Michel Houellebecq. I’ve read everything by him (in English translation); he’s the only author I’m actually looking forward to read much more of.

While waiting for Houllebecq’s next book I restrict my reading to science news, because I find more consolation in learning about how the biosciences can help create a better post-capitalist world. But maybe I should take up my rusty Greek again and read the parallel version of Aristophanes’ The Clouds (I have an unopened copy of the critical edition by Kenneth Dover in my bookcase). I think that’s a better way to enjoy myself here towards the end of my intellectual life.

My first and last fiction books – almost 70 years apart.

My first and last fiction books – almost 70 years apart.