I’ve just spent three days at Deutsches Museum in Munich. Primarily to attend a conference about the relations between research and exhibitions in museums. But I also took the opportunity to see its famous public galleries.

I’ve just spent three days at Deutsches Museum in Munich. Primarily to attend a conference about the relations between research and exhibitions in museums. But I also took the opportunity to see its famous public galleries.

In spite of its name, Deutsches Museum is not about kings or wars or politics etc. — things that so many national museums are obsessed with. In contrast to British Museum, which circles around the treasures acquired from the former Empire, Deutsches Museum focuses on the foundations of German prosperity, that is, its engineering culture. The ~40,000 square meters of exhibition space are filled with electrical generators, brewery equipment, agricultural machinery, cars and airplanes, printing presses, cameras, computers, and so forth.

The museum is one long reminder of the fact that it is materials and technologies rather than ideas and politics that are shaping modern life (for example, agricultural machinery is a major precondition for large-scale urbanisation). A couple of hours’ walk among the thousands of things, machines, gadgets and apparatuses in the galleries gives you a feeling of what has made the modern world go around.

The museum is one long reminder of the fact that it is materials and technologies rather than ideas and politics that are shaping modern life (for example, agricultural machinery is a major precondition for large-scale urbanisation). A couple of hours’ walk among the thousands of things, machines, gadgets and apparatuses in the galleries gives you a feeling of what has made the modern world go around.

Others apparently feel the same way: last Saturday, the museum was full of visitors, mainly grown-ups, even some young chic women in their twenties — in contrast to many other science and technology museum weekend audiences, which are dominated by young children with their parents.

From the point of view of current museological thinking, the museum as a whole is pretty conventional. The large and academically very competent curatorial staff of Deutsches Museum have done a formidable job in acquiring, preserving, describing and arranging a representative collection of the marvels of modern technology. With few exceptions, however, they don’t seem to have listened to the siren calls of New Museology. Even the newest galleries are more like updated version of the classical ones.

Personally, I’m quite fond of old-school museums with tons of systematically ordered things, like classical natural history museums with their amassment of butterflies on needles and stuffed birds from all over the world. Same here: the huge building in central Munich has gallery after gallery displaying one damned machine after the other, each acompanied by a short, precise, informative text. Ordning muss sein.

Some of this is utterly fascinating.  The computer gallery is magnificent, packed with pre-computer age calculating machines, early mainframe computers, integrated circuits, and devices with chips — a must for computer history afficionadoses. Likewise, the new gallery on the history of photo and film technology (curated by Cornelia Kemp) with its central 20 meter long, double-sided glass cabinet with hundreds of still and movie cameras, from mid-19th century to the present, gives a fantastic snapshot (!) of the chronological development of camera devices.

The computer gallery is magnificent, packed with pre-computer age calculating machines, early mainframe computers, integrated circuits, and devices with chips — a must for computer history afficionadoses. Likewise, the new gallery on the history of photo and film technology (curated by Cornelia Kemp) with its central 20 meter long, double-sided glass cabinet with hundreds of still and movie cameras, from mid-19th century to the present, gives a fantastic snapshot (!) of the chronological development of camera devices.

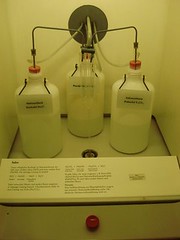

Other parts of the museum are more problematic. The chemistry galleries, with their didactic interactive showcases where visitors are supposed to do ‘experiments’ by pressing buttons, are quite hopeless. (On the other hand, these showcases have a kind of retro quality that speaks in favour of keeping them as museum pieces in their own right — as examples of informal learning in the 1970s).

Other parts of the museum are more problematic. The chemistry galleries, with their didactic interactive showcases where visitors are supposed to do ‘experiments’ by pressing buttons, are quite hopeless. (On the other hand, these showcases have a kind of retro quality that speaks in favour of keeping them as museum pieces in their own right — as examples of informal learning in the 1970s).

Yet, even this colossus of a classical history of technology museum has its innovative moments. I’ll be back with a few more reflections in the next couple of days.